对评论区追问的回答:

「请教一下,阵痛和抗炎这两个词经常被放在一起说,这两个词有什么联系、区别呢?比如说短期的急性无菌性关节炎,NSAID到底只是单纯止痛最终靠自愈,还是额外有加速痊愈的效果呢?」

答:这要扯到「炎症」的定义和「镇痛」的定义以及病理生理学了。

炎症并不一定是「感染」。痛是炎症的局部反应之一, 发热是全身反应之一,功能障碍是炎症的局部反应之一, 也是造成患者生活质量下降和自尊下降的主要原因。

十二年前卫生部7月16日通知,在医疗诊疗科目名录中增加疼痛科诊疗科目。非甾体解热镇痛药或非甾体抗炎药(NSAIDs)是具有抗炎镇痛作用但无甾体结构的药物的集合,已有三千多年的历史。NSAIDs的特点是类别与品种多、作用靶位相同、不良反应基本相似、应用十分广泛。

上课一般不提的内容是, 甾体的「甾」字是一个象形文字。 正如俺自创的 )x( 格的 )x( 字和 )!( 人的 )!( 字, 都是截石位才能领会到的象形文字。甾」字代表 类固醇(Steroid) ,由3个碳环己烷(A、B、C)和1个碳环(D)组成的稠合四环化合物。天然类固醇分子中的六碳环A、B、C都呈椅式构象(环己烷结构),这是最稳定的构象(唯一的例外是雌激素分子内的A环是芳香环为平面构象)。「甾」字的字形,形象化地表述了这类化合物共通的结构特徵:三条屈线代表三条支链,「田」字形代表四个环。

国际疼痛学会将疼痛定义为「由于事实上或潜在的组织损伤所引起的不愉快感觉和情绪体验。」对于疼痛的治疗必须是综合性的,包括药物治疗、心理治疗和物理治疗。

NSAIDs 一般不会影响病程的长短。 因此不会有「加速痊愈的效果」。

但是,

疼痛可以扯上相对论, 因为疼痛发生的过程中患者会觉得时间过得非常非常慢. 同时,疼痛对于普通患者是一种心理折磨,可以导致心理疾病。因此, NSAIDs 虽然不会影响病程的长短,但是可以在心理上减少折磨, 主观上让患者有「加速痊愈的效果」, 同时提升生活质量和自尊。

药物治疗疼痛的原则是

NSAIDs种类很多,最具代表性的是三类药物

「镇痛药」(Analgesic)的定义在英文里面很简单, 玩过电脑游戏的都知道 PAINKILLER 就是「镇痛」药。当然,您可以理解为治标不治本。

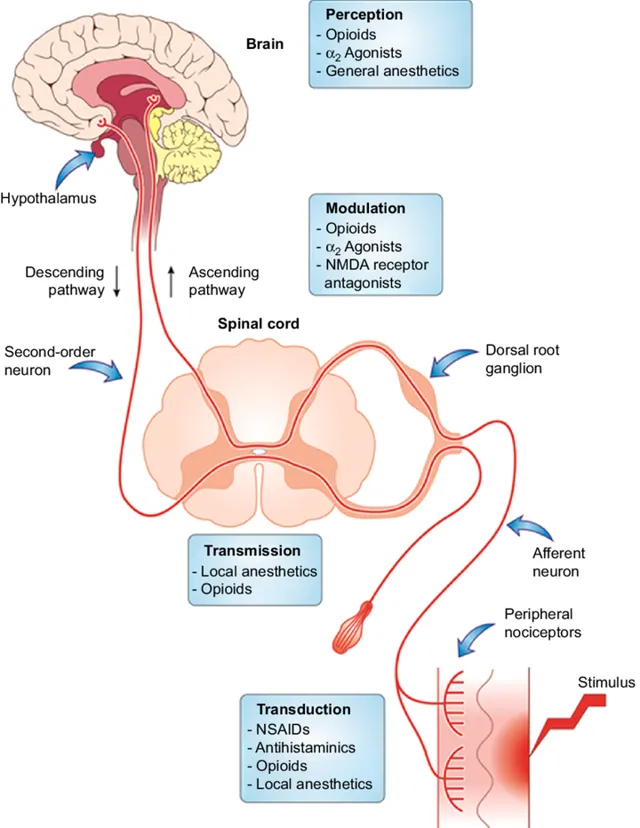

可是, 很多疾病不存在治本或者治本的成本太高。镇痛是指能缓解疼痛的一类药物。Analgesic 的辞源来自希腊语的"an"(即「无」)和"algos"(即「痛」)。镇痛药通过不同的机理作用于中枢和周围神经系统,对痛觉通路(包括化学)有选择性抑制或者阻断作用,但对其他感觉中枢微少。

「无菌性关节炎」

「无菌性炎症」是人体发生机体障碍疾病和顽固疼痛的部位没有细菌感染,病理检查和组织切片找不到任何微生物侵害的迹象,从病理变化上来看是无菌性的,没有病源菌的炎症,因而抗生素治疗无效。比如一些运动系统疾病,如关节炎、纤维组织炎、腱鞘炎、强直性脊柱炎等,不是病原微生物引起,没必要用抗菌治疗,同时激进的外科治疗的破坏性以及侵入性相比带来的益处更大。保守的药物治疗是更容易为患者接受的治疗选择。

既然有非甾体抗炎药(NSAID), 那就有 甾体类抗炎药 。甾体类抗炎药(又叫 糖皮质激素 )具有消炎、抗过敏、抗休克和退热等多种作用。

因此,甾体类抗炎药被用于治疗炎症性疾病,如类风湿性关节炎等自身免疫性疾病。 糖皮质激素 / 甾体类抗炎药本身无镇痛作用 ,主要包括泼尼松、氢化可的松、地塞米松(俗称「地米」)等。糖皮质激素可通过抑制炎症介质合成、抑制炎症细胞迁移与增强抗炎细胞因子合成等机制抑制炎症反应。

如果好奇,那么了解多一点也无妨。既然有糖皮质激素, 就有盐皮质激素, 盐皮质激素(mineralocorticoid) 是由肾上腺皮质球状带细胞分泌的类固醇激素,主要生理作用是维持人体内水和电解质的平衡。

地塞米松(俗称「地米」)广为中国人知晓是因为 2003 年的「飞典」,具体就不说了, 这是个农夫和蛇的故事。

炎症并不一定是「感染」。

痛是炎症的局部反应之一, 发热是全身反应之一,功能障碍是炎症的局部反应之一, 也是造成患者生活质量下降和自尊下降的主要原因。

炎症的概念

1、炎症的定义:是具有血管系统的活体组织对损伤因子所发生的一种防御反应。血管反应是炎症过程的中心环节。

2、炎症的局部表现和全身反应

(1)局部反应:红、肿、热、痛、功能障碍。

(2)全身反应:发热、末梢血白细胞升高。

3、炎症反应的防御作用:防御作用和损伤作用共存。

炎症的原因:

1、物理性因子

2、化学性因子

3、生物性因子

4、坏死组织

5、变态反应或异常免疫反应

炎症的局部基本病理变化

炎症的基本病理变化包括变质(alteration)、渗出(exudation)和增生(proliferation)。

一、变质:炎症局部组织发生的变性和坏死。

二、渗出:炎症局部组织血管内的液体和细胞成分,通过血管壁进入组织间质、体腔、粘膜表面和体表的过程。渗出是炎症最具特征性的变化。

1、血流动力学改变

2、血管通透性增加

(1)内皮细胞收缩

(2)内皮细胞损伤

(3)新生毛细血管的高通透性

3、渗出液的作用:

局部炎症性水肿有稀释毒素,减轻毒素对局部的损伤作用;为局部浸润的白细胞带来营养物质和带走代谢产物;渗出物中所含的抗体和补体有利于消灭病原体;渗出物中的纤维蛋白原所形成的纤维蛋白交织成网,限制病原微生物的扩散,有利于白细胞吞噬消灭病原体,炎症后期,纤维网架可成为修复支架,并利于成纤维细胞产生胶原纤维;渗出物中的病原微生物和毒素随淋巴液被带到局部淋巴结,有利于产生细胞和体液免疫;渗出液过多有压迫和阻塞作用,渗出物中的纤维素如吸收不良可发生机化。

4、白细胞的渗出和吞噬作用

(1)白细胞边集

(2)白细胞粘着

(3)白细胞游出和化学趋化作用

(4)白细胞的局部作用:吞噬作用,免疫作用,组织损伤作用。

5、炎症介质在炎症过程中的作用

(1)细胞释放的炎症介质:血管活性胺(组胺和5-羟色胺)、花生四烯酸代谢产物、白细胞产物、细胞因子和化学因子、血小板激活因子、NO及神经肽。

(2)体液中的炎症介质:激肽系统、补体系统、凝血系统、纤溶系统。

三、增生:包括实质细胞(如鼻粘膜上皮细胞和腺体细胞)和间质细胞(巨噬细胞、血管内皮细胞、成纤维细胞)的增生。

炎症的经过和结局

一、炎症的经过

1、急性炎症的特点:局部表现为红、肿、热、痛、功能障碍,全身表现为发热、末梢血白细胞计数增加。

2、慢性炎症的特点:持续几周或几月,可发生在急性炎症之后或潜隐逐渐发生。

二、炎症的结局

(一)痊愈

1、完全愈复

2、不完全愈复

(二)迁延为慢性炎症

(三)蔓延扩散

1、局部蔓延

2、淋巴道蔓延

3、血行蔓延:

(1)菌血症(becteremia);细菌从局部病灶入血,并从血中查到细菌。

(2)毒血症(toxemia);细菌毒素吸收入血,机体有明显中毒症状。

(3)败血症(septicemia);致病力强的细菌入血后,在大量繁殖的同时产生毒素,机体有明显中毒症状。

(4)脓毒败血症(pyemia):化脓性细菌引起的败血症。

炎症的类型

一、炎症的一般分类原则:概括的分为变质性炎、渗出性炎和增生性炎。

二、变质性炎:以变质变化为主的炎症,渗出和增生改变较轻微,多见于急性炎症。

1、部位:肝、肾、心和脑等实质性器官。

2、疾病举例:急性重型肝炎,流行性乙型脑炎。

三、渗出性炎:以浆液、纤维蛋白原和嗜中性粒细胞渗出为主的炎症,多为急性炎症。

(一)浆液性炎:以浆液渗出为其特征。

1、部位:发生于粘膜——浆液性卡他性炎

浆膜——体腔积液

疏松结缔组织——局部炎性水肿

2、对机体的影响

(二)纤维素性炎:以纤维蛋白原渗出为主,继而形成纤维素。HE切片中纤维素呈红染交织的网状、条状或颗粒状。

1、部位:发生于粘膜——假膜性炎

浆膜——如「绒毛心」

肺组织——见于大叶性肺炎

2、对机体的影响

(三)化脓性炎:以嗜中性粒细胞渗出为主,并有不同程度的组织坏死和脓液形成为特点。

1、表面化脓和积脓(empyema)

2、蜂窝织炎(phlegmonous inflammation):指疏松结缔组织的弥漫性化脓性炎,常发生于皮肤、肌肉和阑尾。主由溶血性链球菌引起。

3、脓肿(abscess):指局限性化脓性炎,可发生于皮下和内脏。主由金黄色葡萄球菌引起。

4、出血性炎(hemorrhagic inflammation)

上述各型炎症可单独发生,亦可合并存在。

四、增生性炎

(一)非特异性增生性炎

(二)肉芽肿性炎(granulomatous inflammation):以肉芽肿形成为其特点,多为特殊类型的慢性炎症。

1、肉芽肿的定义:由巨噬细胞及其演化的细胞,呈限局性浸润和增生所形成的境界清楚的结节状病灶。

2、常见病因

3、肉芽肿的形成条件和组成

(1)异物性肉芽肿

(2)感染性肉芽肿

4、肉芽肿性炎病理变化:

以结核结节为例:中央——干酪样坏死

周围——放射状排列的上皮细胞

可见郎罕氏巨细胞

外围——淋巴细胞、纤维结缔组织

布洛芬是一种非甾体解热镇痛药(NSAID),具有一定的 「消炎作用」 。用于缓解疼痛、发烧和炎症,包括痛经、偏头痛和类风湿性关节炎。也可用于关闭早产儿的动脉导管未闭。

布洛芬常见的副作用包括胃灼热和皮疹。

与其他非甾体解热镇痛药相比,布洛芬可能有其他副作用,如胃肠道出血。

布洛芬会增加心力衰竭、肾衰竭和肝衰竭的风险。低剂量时,布洛芬似乎不会增加心脏病发作的风险;但剂量较大时,可能会增加心脏病发作的风险。 布洛芬还可能加重哮喘。 虽然布洛芬对怀孕早期的安全性尚不明确,但布洛芬似乎对怀孕晚期有害,因此不建议在怀孕晚期使用布洛芬。

布洛芬通过降低环氧化酶(COX)的活性来抑制前列腺素的产生。

布洛芬主要用于治疗发热(包括疫苗接种后)、轻度至中度疼痛(包括术后止痛)、痛经、骨关节炎、牙痛、头痛和肾结石引起的疼痛。约 60% 的人对任何一种非甾体解热镇痛药都有反应;对某种药物反应不佳的人可能会对另一种药物有反应。Cochrane 对 51 项非甾体解热镇痛药治疗下背痛的试验进行了医学回顾,发现 "非甾体解热镇痛药对急性下背痛患者的短期症状缓解有效"。

**布洛芬在治疗椎间盘脱出方面可能不如纳普生和肌松药

2006 年,美国食品和药物管理局(FDA)批准布洛芬赖氨酸用于关闭胎龄不超过 32 周、体重介于 500-1,500 克(1-3 磅)之间的早产儿的动脉导管未闭,此时通常的药物治疗(如限制输液、利尿剂和呼吸支持)无效。

布洛芬不良反应

布洛芬不良反应包括恶心、消化不良、腹泻、便秘、胃肠道溃疡、头痛、头晕、皮疹、盐和液体潴留以及高血压。

布洛芬不常见的不良反应包括食道溃疡、心力衰竭、高血钾、肾功能损害、精神错乱和支气管痉挛。

布洛芬可在血液、血浆或血清中定量,以证明过敏反应患者体内存在该药物,确诊住院患者中毒,或协助医学死亡调查。布洛芬血浆浓度、摄入时间和过量服药者发生肾毒性的风险相关的专著已经出版。2020 年 10 月,美国 FDA 要求更新所有非甾体解热镇痛药的药品标签,以说明羊水过少会导致未出生婴儿出现肾脏问题的风险。

心血管风险

与其他几种非甾体解热镇痛药一样,长期服用布洛芬也会导致女性患上高血压的风险,尽管这种风险低于扑热息痛(对乙酰氨基酚)和心肌梗死(心脏病发作),尤其是在长期服用较大剂量的人群中。2015 年 7 月 9 日,美国 FDA 强化了布洛芬和相关非甾体解热镇痛药增加心脏病发作和中风风险的警告;非甾体解热镇痛药阿司匹林不在警告之列。

皮肤

与其他非甾体解热镇痛药一样,布洛芬也被报告为光敏剂,但与其他2-芳基丙酸类药物相比,布洛芬被认为是一种弱光敏剂。与其他非甾体解热镇痛药一样,布洛芬也是导致自身免疫性疾病史蒂文斯-约翰逊综合征(SJS)的极其罕见的原因。

相互作用

酒精:服用布洛芬时饮酒可能会增加胃出血的风险。

阿司匹林:据美国食品及药物管理局称,"布洛芬会干扰小剂量阿司匹林的抗血小板作用,可能会降低阿司匹林用于保护心脏和预防中风的效果"。在布洛芬和速释(IR)阿司匹林的剂量之间留出足够的间隔时间可以避免这一问题。建议在服用布洛芬和服用阿司匹林之间间隔的时间取决于先服用哪种药物。如果在服用 IR 阿司匹林后服用布洛芬,间隔时间应为 30 分钟或更长;如果在服用 IR 阿司匹林前服用布洛芬,间隔时间应为 8 小时或更长。不过,对于肠溶阿司匹林,不建议采用这种时间安排。不过,如果布洛芬只是偶尔服用,而不按照推荐的时间服用,那么每日服用阿司匹林对心脏保护和中风预防的作用就会减弱到最低程度。

扑热息痛:布洛芬与扑热息痛合用被认为对儿童短期服用基本安全。

用药过量:自布洛芬获准在非处方药中使用以来,布洛芬用药过量已成为常见现象。尽管布洛芬用药过量引起危及生命的并发症的频率很低,但医学文献中报道了许多用药过量的经历。大多数症状是布洛芬药理作用的过度,包括腹痛、恶心、呕吐、嗜睡、头晕、头痛、耳鸣和眼球震颤。极少数情况下会出现更严重的症状,如消化道出血、癫痫发作、代谢性酸中毒、高钾血症、低血压、心率减慢、心率加快、心房颤动、昏迷、肝功能异常、急性肾衰竭、紫绀、呼吸抑制和心跳骤停。一般来说,过量服用布洛芬所出现的症状与过量服用其他非甾体解热镇痛药所引起的症状相似。

症状的严重程度与测得的布洛芬血浆水平之间的相关性很弱。剂量低于 100 毫克/千克时,不太可能出现毒性反应,但超过 400 毫克/千克(对普通人而言,200 毫克单位的布洛芬约为 150 片)时,毒性反应可能会很严重;不过,大剂量并不表明临床过程可能会致命。

治疗布洛芬过量的方法取决于症状的表现。如果症状出现较早,建议对胃部进行净化。这可以使用活性炭来实现;活性炭可以在药物进入血液之前将其吸收。洗胃现在已很少使用,但如果摄入量可能危及生命,可以考虑洗胃,洗胃可在摄入后 60 分钟内进行。不建议进行有目的的呕吐。[50] 大部分布洛芬摄入只会产生轻微的影响,过量摄入的处理方法也很简单。应采取标准措施维持正常尿量,并监测肾功能。由于布洛芬具有酸性,也会随尿液排出体外,因此强制碱性利尿理论上是有益的。然而,由于布洛芬在血液中与蛋白质高度结合,肾脏对未改变药物的排泄微乎其微。因此,强制碱性利尿的益处有限。

流产:加拿大一项针对孕妇的研究表明,服用任何类型或数量的非甾体解热镇痛药(包括布洛芬、双氯芬酸和纳普生)的孕妇流产的几率是未服药孕妇的 2.4 倍。

药理学

布洛芬等非甾体解热镇痛药通过抑制环氧化酶(COX)发挥作用,COX 可将花生四烯酸转化为前列腺素 p(PGp)。而 PGp 又会被其他酶转化为其他几种前列腺素(疼痛、炎症和发烧的介质)和血栓素 A2(刺激血小板聚集,导致血栓形成)。

与阿司匹林和吲哚美辛一样,布洛芬也是一种非选择性 COX 抑制剂,它能抑制环氧化酶的两种异构体 COX-1 和 COX-2。非甾体解热镇痛药的镇痛、解热和抗炎活性似乎主要通过抑制 COX-2,从而减少参与介导炎症、疼痛、发热和肿胀的前列腺素的合成。解热作用可能是由于对下丘脑的作用,导致外周血流增加、血管扩张以及随后的散热。然而,COX-1 各异构体在非甾体解热镇痛药的镇痛、抗炎和胃损伤作用中的作用尚不确定,不同化合物造成的镇痛和胃损伤程度也不同。

布洛芬是一种外消旋混合物。R-对映体在体内会大量相互转化为 S-对映体。S 对映体被认为是药理活性更强的对映体。R 对映体通过一系列三种主要酶进行转化。这些酶包括酰基-CoA-合成酶,它将 R-对映体转化为 (-)-R-ibuprofen I-CoA;2-芳基丙酰基-CoA 外切酶,它将 (-)-R-ibuprofen I-CoA 转化为 (+)-S-ibuprofen I-CoA;水解酶,它将 (+)-S-ibuprofen I-CoA 转化为 S-对映体。 [42] 除了将布洛芬转化为 S-对映体外,人体还可将布洛芬代谢为其他几种化合物,包括大量羟基、羧基和葡萄糖醛酸代谢物。几乎所有这些代谢物都没有药理作用。

与大多数其他非甾体解热镇痛药不同,布洛芬还是 Rho 激酶的抑制剂,可能有助于脊髓损伤后的恢复 另一个不寻常的活性是抑制甜味受体。

药代动力学

口服布洛芬后,1-2 小时后血清浓度达到峰值,多达 99% 的药物与血浆蛋白结合。大部分布洛芬在 24 小时内代谢并随尿液排出体外;然而,1% 的未改变药物通过胆汁排泄排出体外。

化学:布洛芬几乎不溶于水,但极易溶于大多数有机溶剂,如乙醇(90% EtOH 在 40 °C 时为 66.18 克/100 毫升)、甲醇、丙酮和二氯甲烷. 布洛芬与酮洛芬、氟比洛芬和萘普生等其他 2-芳基丙酸酯衍生物一样,在丙酸酯分子的 α 位含有一个立体中心。药店出售的产品是 S 和 R 异构体的外消旋混合物。S(右旋)异构体的生物活性更高;这种异构体已被分离出来并用于医疗(详见右布洛芬)。

其他:由于布洛芬具有抗炎特性,因此有时会被用于治疗痤疮,在日本,布洛芬还被用于治疗成人痤疮的局部用药。与其他非甾体解热镇痛药一样,布洛芬也可用于治疗严重的正性低血压(站立时血压低)。布洛芬(Ibuprofen)与降低帕金森病的风险有关,并可延缓或预防帕金森病。阿司匹林、其他非甾体解热镇痛药和扑热息痛(对乙酰氨基酚)对帕金森病的发病风险没有影响。2011 年 3 月,哈佛医学院的研究人员在【神经学】杂志上宣布,布洛芬对帕金森病的发病风险具有神经保护作用。据报道,经常服用布洛芬的人患帕金森病的风险降低了 38%,但其他止痛药(如阿司匹林和扑热息痛)则没有这种效果。考虑到布洛芬可能对泌尿系统和消化系统产生不良影响,在普通人群中使用布洛芬来降低帕金森病的发病风险并非没有问题。

一些膳食补充剂与布洛芬和其他非甾体解热镇痛药同时服用可能会有危险,但截至 2016 年,还需要进行更多的研究才能确定。这些保健品包括能防止血小板聚集的保健品,包括银杏、大蒜、生姜、山桑子、当归、发热草、人参、姜黄、绣线菊(Filipendula ulmaria)和柳叶(Salix spp.);含有香豆素的保健品,包括甘菊、七叶树、葫芦巴和红三叶草;以及会增加出血风险的保健品,如罗望子。

对乙酰氨基酚(Acetaminophen、Paracetamol、APAP),又称乙酰胺酚、扑热息痛或对乙酰氨基酚(USAN)是一种广泛使用的镇痛药和解热药。

扑热息痛是从煤焦油中提取的,是苯乙哌啶的活性代谢产物,但与苯乙哌啶不同的是,对乙酰氨基酚尚未被证实有任何致癌性。

与阿司匹林不同, 扑热息痛不是一种非常有效的消炎药 。扑热息痛的耐受性很好,没有阿司匹林的许多副作用,而且是非处方药,因此 常用于缓解发烧、头痛和其他轻微疼痛 。

扑热息痛还 可用于治疗较严重的疼痛 ,因为它允许合用较低剂量的其他非甾体解热镇痛药(NSAIDs),从而将总体副作用降至最低。它是许多感冒药的主要成分,包括泰诺和必理痛等。在推荐剂量下,人体使用对乙酰氨基酚是安全的;但是,急性过量使用对乙酰氨基酚会造成致命的肝损伤,通常在饮酒后会加重肝损伤,近年来,意外自毒和自杀的人数不断增加。

对乙酰氨基酚(acetaminophen)和扑热息痛(paracetamol)这两个词来源于化合物的化学名称:对乙酰氨基苯酚(para-acetylaminophenol)和对乙酰氨基苯酚(para-acetylaminophenol)(泰诺(Tylenol)这个品牌名称也来源于对乙酰氨基苯酚(para-acetylaminophenol))。

在古代和中世纪,已知的解热剂有白柳树皮中的化合物(这类化学物质被称为水杨素,阿司匹林就是由此发展而来的)和金鸡纳树皮中的化合物。

奎宁本身也具有解热作用。

整个 19 世纪中后期,拜耳公司的化学家费利克斯-霍夫曼(Felix Hoffmann)一直在努力提炼和分离水杨素和水杨酸(法国化学家夏尔-弗雷德里克-格哈特(Charles Frédéric Gerhardt)在 40 年前也完成了这项工作,但他认为不切实际而放弃了这项工作)。

19 世纪 80 年代,金鸡纳树变得稀缺,人们开始寻找替代品。19 世纪 80 年代开发出了两种替代性退烧药:1886 年的乙酰苯胺和 1887 年的苯乙哌啶。1878 年,哈蒙-诺斯罗普-莫尔斯(Harmon Northrop Morse)通过对硝基苯酚与锡在冰醋酸中的还原反应,首次合成了扑热息痛;然而,扑热息痛在此后的 15 年中一直未被用于医疗。1893 年,人们在服用过苯乙哌啶的人的尿液中发现了扑热息痛,并将其浓缩成一种带有苦味的白色结晶化合物。1899 年,人们发现扑热息痛是乙酰苯胺的代谢物。这一发现在当时基本上被忽视了。

1946 年,镇痛和镇静药物研究所向纽约市卫生局提供了一笔研究镇痛剂相关问题的拨款。伯纳德-布罗迪(Bernard Brodie)和朱利叶斯-阿克塞尔罗德(Julius Axelrod)受命调查为什么非阿司匹林类药物与高铁血红蛋白血症的发生有关,高铁血红蛋白血症会降低血液的携氧能力,并可能致命。1948 年,布罗迪和阿克塞尔罗德将使用乙酰苯胺与高铁血红蛋白症联系起来,并确定乙酰苯胺的镇痛效果是由于其活性代谢物扑热息痛所致。他们主张使用扑热息痛,因为它没有乙酰苯胺的毒性作用。1955 年,McNeil Laboratories 首次将扑热息痛作为儿童止痛退烧药出售,品牌名称为 Tylenol Children's Elixir。1956 年,500 毫克扑热息痛片剂在英国上市,商品名为 "Panadol",由斯特林药品公司的子公司 Frederick Stearns & Co 生产。扑热息痛最初只能凭处方购买,用于缓解疼痛和发烧,其广告词是 "对胃温和",因为当时的其他镇痛剂都含有阿司匹林,而阿司匹林是一种已知的胃刺激物。1958 年 6 月,扑热息痛的儿童配方 "Panadol Elixir "上市。1963 年,扑热息痛被列入【英国药典】,作为一种副作用小、与其他药物相互作用小的镇痛剂,扑热息痛自此广受欢迎。对乙酰氨基酚在美国的专利权早已到期,根据 1984 年【药品价格竞争和专利期恢复法案】,该药的仿制药已广泛上市,但某些泰诺制剂在 2007 年之前一直受到保护。

化学结构和反应性

对乙酰氨基酚由一个苯环核心组成,苯环核心被一个羟基和一个对位 (1,4) 模式酰胺基团的氮原子取代。酰胺基为乙酰胺(乙酰胺)。这是一个广泛共轭的体系,因为羟基氧上的孤对、苯π云、氮孤对、羰基碳上的 p 轨道和羰基氧上的孤对都是共轭的。两个活化基团的存在也使苯环对亲电芳香取代具有很高的反应活性。由于取代基之间存在正向、对向和对位的关系,因此苯环上的所有位置或多或少都具有相同的活化性。共轭作用还大大降低了氧原子和氮原子的碱性,同时通过在氧化苯阴离子上形成的电荷分离使羟基呈酸性。

合成:对乙酰氨基酚可通过以下方式从起始原料苯酚中制成

使用硫酸和硝酸钠对苯酚进行硝化(由于苯酚具有高度活化性,与硝化苯所需的发烟硝酸混合物相比,硝化苯酚所需的条件非常温和)。对位异构体通过分馏与正位异构体分离(由于 OH 是邻对定向的,因此元异构体很少)。在碱性介质中使用还原剂(如硼氢化钠)将 4-硝基苯酚还原成 4-氨基苯酚。4-aminophenol 与醋酸酐反应生成扑热息痛。

请注意,对乙酰氨基酚的合成缺乏几乎所有药物合成中固有的一个非常重要的难点: 缺乏立体中心意味着不需要设计立体选择性合成。此外,还有更高效的工业合成方法。

在欧洲、非洲、亚洲、中美洲和澳大拉西亚销售的扑热息痛是最广泛的品牌,在 80 多个国家销售。在北美,扑热息痛以通用名(通常标为对乙酰氨基酚)或多个商品名销售,例如泰诺(McNeil-PPC, Inc)、Anacin-3、Tempra 和 Datril。虽然英国有品牌扑热息痛(如 Panadol),但无品牌或普通扑热息痛的销售更为普遍。

在某些配方中,扑热息痛与阿片类药物可待因合用,有时被称为联合可待因(BAN)。

在美国和加拿大,这种药物以 Tylenol #1/2/3/4 的名称销售,其中分别含有约 1/8 谷、约 1/4 谷、约 1/2 谷和约 1 谷可待因。美国的一粒是 64.78971 毫克--在生产过程中通常会四舍五入到 5 毫克的倍数(因此 3 号含有 30 毫克,4 号含有 60 毫克,而 1 号可能是 8 毫克或 10 毫克,具体取决于生产商)。

在美国,这种复方制剂只能凭处方购买,而在加拿大,最低强度的复方制剂是非处方药,在其他国家,其他强度的复方制剂也可以非处方药购买。此外,还有非专利药。在英国和许多其他国家,这种复方制剂在市场上的名称是 Tylex CD 和 Panadeine。其他名称包括 Captin、Disprol、Dymadon、Fensum、Hedex、Mexalen、Nofedol、Paralen、Pediapirin、Perfalgan 和 Solpadeine。

扑热息痛还可与其他阿片类中枢镇痛药物合用,如双氢可待因(称为 co-dydramol (BAN))、羟考酮或氢可酮,在美国市场上分别称为 Percocet 和 Vicodin。另一种非常常用的镇痛药组合包括扑热息痛与丙氧芬纳西酸盐的组合,以 Darvocet 品牌销售。扑热息痛、可待因和镇静剂琥珀酸多西拉敏的复方制剂在市场上以 Syndol 或 Mersyndol 出售。

扑热息痛常用于治疗偏头痛的多成分制剂,通常包括含有或不含咖啡因的丁达尔和对乙酰氨基酚,有时还含有可待因。

扑热息痛通常以片剂、液体混悬剂、栓剂、静脉注射或肌肉注射形式给药。成人常用剂量为 500 毫克至 1000 毫克。建议成人每日最大剂量为 4 克。在推荐剂量下,扑热息痛对儿童和婴儿以及成人都是安全的。

作用机制

扑热息痛的退烧和止痛机制仍存在争议。

造成这种混淆的原因主要是扑热息痛能减少前列腺素--炎症化学物质的产生。阿司匹林也能抑制前列腺素的产生,但与阿司匹林不同的是,扑热息痛的消炎作用并不大。同样,阿司匹林能抑制促进凝血的化学物质血栓素的产生,而扑热息痛却不能。

众所周知,阿司匹林能抑制环氧化酶(COX)家族的酶,而扑热息痛与阿司匹林的作用部分相似,因此很多研究都集中在扑热息痛是否也能抑制 COX。不过,现在已经明确的是,扑热息痛(至少)通过两种途径发挥作用。

COX 家族的酶负责将花生四烯酸代谢为前列腺素 p(一种不稳定的分子),而前列腺素 p 又会转化为许多其他促炎化合物。传统的非甾体解热镇痛药,会阻断这一步骤。研究表明,扑热息痛可减少 COX 酶的氧化形式,防止其形成促炎化学物质。

扑热息痛会代谢为 AM404,这是一种具有多种作用的化合物;最重要的是,它能抑制神经元摄取内源性大麻素/香草酰胺。安乃近酰胺的摄取会导致人体的主要疼痛受体(痛觉感受器)TRPV1(旧名:香草素受体)被激活。此外,AM404 还能抑制钠通道,这与麻醉剂利多卡因和普鲁卡因的作用类似。

这些作用中的任何一种本身都已被证明能减轻疼痛,是扑热息痛的一种可能机制,但有研究表明,在阻断大麻素受体从而使大麻素再摄取的任何作用失去意义后,扑热息痛不再具有任何镇痛效果,这表明其镇痛作用确实是由内源性大麻素系统介导的。

扑热息痛抑制环氧化酶家族的 COX-3 异构体,这种酶在狗体内表达时与其他 COX 酶非常相似,会产生促炎化学物质,并被扑热息痛选择性地抑制。然而,在人类和小鼠体内,COX-3 酶没有炎症作用,也不受扑热息痛的调节。

代谢:扑热息痛代谢过程中涉及的反应。

扑热息痛主要在肝脏中代谢,其主要代谢产物包括无活性的硫酸盐和葡萄糖醛酸苷结合物,这些物质由肾脏排出体外。只有少量的对乙酰氨基酚通过肝脏细胞色素 P450 酶系统(其 CYP2E1 和 CYP1A2 同工酶)进行代谢,这种少量的烷基化代谢物(N-乙酰对苯醌亚胺,缩写为 NAPQI)导致了对乙酰氨基酚的毒性作用。

P450 基因存在大量多态性,CYP2D6 的遗传多态性已被广泛研究。根据 CYP2D6 的表达水平,可将人群分为 "广泛代谢者"、"超快速代谢者 "和 "不良代谢者"。CYP2D6 也可能有助于 NAPQI 的形成,尽管其程度低于其他 P450 同工酶,其活性可能会导致扑热息痛的毒性,尤其是在广泛代谢者和超快速代谢者中,以及在服用扑热息痛的剂量非常大时。

扑热息痛的代谢是中毒的一个很好的例子,因为造成中毒的主要是代谢产物 NAPQI,而不是扑热息痛本身。在美国,过量服用扑热息痛导致向毒物控制中心拨打的电话比过量服用任何其他药物都要多,每年因急性肝功能衰竭而拨打的电话超过 100,000 个,急诊就诊 56,000 人次,住院 2,600 人次,死亡 458 人次。

在通常剂量下,有毒代谢物 NAPQI 会通过与谷胱甘肽的巯基不可逆地结合或服用 N-乙酰半胱氨酸等巯基化合物迅速解毒,生成无毒的共轭物,最终由肾脏排出体外。

与非甾体解热镇痛药的比较

扑热息痛与阿司匹林和布洛芬等其他常见镇痛药不同, 它的抗炎活性相对较低,因此不被视为抗炎药。

疗效:在疗效比较方面,与其他非甾体解热镇痛药相比,研究结果存在矛盾。

一项针对成人骨关节炎引起的慢性疼痛的随机对照试验发现,扑热息痛和布洛芬的疗效相似。然而,一项针对儿童急性肌肉骨骼疼痛的随机对照试验发现,标准 OTC 剂量的布洛芬(400 毫克)比标准剂量的扑热息痛(1000 毫克)更能缓解疼痛。

不良反应:在推荐剂量下,扑热息痛不会刺激胃黏膜,不会像非甾体抗炎药那样影响血液凝固,也不会影响肾脏功能。然而,一些研究表明,大剂量使用(每天超过 2000 毫克)确实会增加上消化道并发症的风险。

扑热息痛在孕期是安全的,不会像非甾体抗炎药那样影响胎儿动脉导管的闭合。与阿司匹林不同,扑热息痛对儿童是安全的,因为扑热息痛与患病毒性疾病儿童的雷氏综合征风险无关。

与其他非甾体解热镇痛药和阿片类镇痛药不同,扑热息痛不会以任何方式引起兴奋或改变情绪。扑热息痛和非甾体抗炎药的好处是不上瘾、不依赖,耐受和戒断的风险较低,但与阿片类药物不同的是,它们可能会损害肝脏;不过,一般来说,与上瘾的危险相比,这一点已被考虑在内。

扑热息痛,尤其是与弱阿片类药物合用时,比其他非甾体解热镇痛药更容易引起反跳性头痛(用药过量性头痛),但比麦角胺或治疗偏头痛的三苯氧胺类药物的风险要小。

毒性:许多制剂(包括非处方药和处方药)中都含有扑热息痛。小剂量扑热息痛对某些动物(如猫)具有毒性。如果不及时治疗,过量服用扑热息痛可导致肝功能衰竭,并在数天内死亡;在美国和英国,扑热息痛中毒是迄今为止导致急性肝功能衰竭的最常见原因。有时,那些不知道扑热息痛引起的中毒会导致较长的时间过程和较高的发病率(重大疾病的可能性)的幸存者会使用扑热息痛企图自杀。

在英国,非处方扑热息痛在药店的销售限制为每包 32 片,在非药店的销售限制为每包 16 片。一次交易最多可售出 100 片,但在药店只能售出 32 片,更多药片由药剂师酌情决定。爱尔兰限制分别为 24 片和 12 片。澳大利亚扑热息痛片在超市有小包装出售,而对于儿童制剂,超过 48 片的包装和栓剂则仅限于药店出售。

作用机制:

扑热息痛大部分通过第二阶段代谢与硫酸盐和葡萄糖醛酸结合转化为非活性化合物,小部分通过细胞色素 P450 酶系统氧化。细胞色素 P450 2E1 (CYP2E1) 和 3A4 (CYP3A4) 会将扑热息痛转化为一种高反应性的中间代谢产物--N-乙酰对苯醌亚胺(NAPQI)。

在正常情况下,NAPQI 可通过与谷胱甘肽共轭而解毒。在对乙酰氨基酚中毒的情况下,硫酸盐和葡萄糖醛酸途径会变得饱和,更多的对乙酰氨基酚会被分流到细胞色素 P450 系统以产生 NAPQI。结果,肝细胞中的谷胱甘肽供应耗尽,NAPQI 可以自由地与细胞膜分子发生反应,导致肝细胞大面积损伤和死亡,引发急性肝坏死。在动物实验中,肝脏谷胱甘肽必须消耗到正常水平的 70% 以下,才会出现肝毒性。

中毒剂量:扑热息痛的毒性剂量变化很大。对于 6 岁以上的人,在 24 小时内单次摄入超过 200 毫克/千克的剂量就有可能引起中毒。如果一个人在 48 小时内摄入了大量扑热息痛,那么在随后的 24 小时内摄入超过 6 克或 150 毫克/千克的剂量就可能导致中毒。如果在 24 小时内多次摄入小剂量的扑热息痛,甚至长期摄入低至 4 克/天的剂量,也可能导致中毒,甚至在摄入低至 6 克/天的剂量时就会死亡。饮酒也会导致小剂量中毒。对于 6 岁及以下儿童,急性剂量超过 10 克或 200 毫克/千克就有可能导致中毒。儿童急性过量服用扑热息痛很少导致疾病或死亡,慢性、超治疗剂量才是儿童中毒的主要原因。

正常剂量的扑热息痛一天四次,每次 1 克,三分之一的患者肝功能检测值可能会增加到正常值的三倍。

由于扑热息痛经常与其他药物一起服用,因此在检查一个人的剂量是否有毒时,必须将所有来源的扑热息痛都包括在内。扑热息痛除了单独出售外,还可能被添加到各种止痛药和感冒药的配方中,以增加药物的止痛效果,有时还会与氢可酮等阿片类药物混合使用,以阻止人们娱乐性地使用扑热息痛或对阿片类药物上瘾。事实上,扑热息痛对人类造成的伤害,无论是致命的过量用药还是慢性肝中毒,都可能远远超过阿片类药物本身造成的伤害。

风险因素:长期过量饮酒会诱导 CYP2E1,从而增加扑热息痛的潜在毒性。因此,在不涉及胃刺激等其他因素的情况下,通常建议使用阿司匹林或布洛芬等止痛药,而不是扑热息痛来缓解宿醉。

空腹是一个危险因素,可能是因为肝脏谷胱甘肽储备耗竭。

文献记载,同时使用 CYP2E1 诱导剂异烟肼会增加肝中毒的风险,但 2E1 诱导是否与本病例中的肝中毒有关尚不清楚。同时使用其他诱导 CYP 酶的药物,如抗癫痫药(包括卡马西平、苯妥英和巴比妥酸盐)也是风险因素之一。

一般来说,过量服用扑热息痛的患者在最初的 24 小时内没有特殊症状。虽然最初可能会出现恶心、呕吐和全身舒张,但这些症状一般会在数小时后缓解。这些症状缓解后,患者往往会感觉好些,并可能认为最糟糕的情况已经过去。如果吸收了有毒剂量,在短暂的相对健康后,患者会出现明显的肝功能衰竭。在大量过量服用的情况下,肝功能衰竭前可能会出现昏迷和代谢性酸中毒。

一般来说,肝细胞在代谢扑热息痛时会发生损伤。在极少数情况下,也会出现急性肾功能衰竭。这通常是由肝肾综合征或多器官功能障碍综合征引起的。急性肾衰竭也可能是中毒的主要临床表现。在这些情况下,有人认为肾脏产生的毒性代谢物多于肝脏。

扑热息痛中毒的预后因剂量和适当的治疗而异。在某些病例中,大量肝坏死会导致暴发性肝功能衰竭,并发出血、低血糖、肾功能衰竭、肝性脑病、脑水肿、败血症、多器官衰竭,并在数天内死亡。在许多病例中,肝坏死可能会持续一段时间,肝功能可能会恢复,病人可能会存活下来,肝功能在几周内恢复正常。

扑热息痛中毒治疗

初步措施: 对无并发症的扑热息痛过量的初步治疗与大多数其他过量治疗类似,都是进行胃肠道净化。此外,解毒剂乙酰半胱氨酸也发挥着重要作用。正常情况下,胃肠道对扑热息痛的吸收在两小时内完成,因此在这段时间内进行净化最有帮助。如果与食物一起摄入,吸收可能会有所减慢。在胃肠道净化方面,医生有很大的判断余地;活性炭吸附是最常用的方法;不过,如果摄入量可能危及生命,并且可以在摄入后 60 分钟内进行洗胃,也可以考虑洗胃。

活性炭能吸附扑热息痛,减少其胃肠道吸收。与洗胃相比,使用活性炭的吸入风险也更小。在使用这种方法之前,人们不愿意在扑热息痛用药过量时使用活性炭,因为担心活性炭也会吸收乙酰半胱氨酸。研究表明,当同时服用乙酰半胱氨酸时,口服乙酰半胱氨酸的吸收率不超过 39%。

不过,如果患者因同时摄入药物而导致胃排空延迟,或在摄入缓释或缓释扑热息痛制剂后摄入药物,则可考虑在此之后再服用活性炭。如果同时摄入的药物需要进行净化,也应使用活性炭。关于服用活性炭后是否要改变口服乙酰半胱氨酸的剂量,甚至是否需要改变乙酰半胱氨酸的剂量,目前存在相互矛盾的建议。

乙酰半胱氨酸: 乙酰半胱氨酸(又称 N-乙酰半胱氨酸或 NAC)通过提供巯基(主要以谷胱甘肽的形式存在,它是谷胱甘肽的前体)与有毒的 NAPQI 代谢物发生反应,从而降低扑热息痛的毒性,使其不会损害细胞并安全排出体外。(在美国,NAC 可作为膳食补充剂购买)。

如果患者在过量服用扑热息痛后不到 8 小时就出现症状,那么乙酰半胱氨酸可大大降低严重肝中毒的风险。如果在摄入超过 8 小时后才开始服用 NAC,其疗效就会急剧下降,因为肝脏内的一系列毒性反应已经开始,急性肝坏死和死亡的风险也会急剧增加。在临床实践中,如果患者在过量服用扑热息痛超过 8 小时后才就诊,那么活性炭很可能不起作用,此时应立即开始使用乙酰半胱氨酸。在较早的情况下,医生可以在患者到达后立即给予活性炭,开始注射乙酰半胱氨酸,并等待实验室检测扑热息痛的浓度。在美国,静脉注射(IV)和口服给药被认为同样有效。但在澳大利亚和英国,静脉注射是唯一推荐的途径。口服乙酰半胱氨酸的剂量为 140 毫克/千克负荷剂量,然后每四小时一次,每次 70 毫克/千克,共 17 次。口服乙酰半胱氨酸的耐受性可能较差,因为它有难闻的味道和气味,而且容易引起恶心和呕吐。可将乙酰半胱氨酸从市场上销售的 10%或 20%的溶液稀释为 5%的溶液,以改善其适口性。需要口服乙酰半胱氨酸时,通常口服乙酰半胱氨酸吸入制剂(Mucomyst)。医院药剂师也可以稀释呼吸用制剂并过滤消毒后供静脉注射使用,但这种做法并不常见。如果因为摄入了另一种药物而需要重复服用碳,那么碳和乙酰半胱氨酸的后续剂量应每两小时错开一次。静脉注射乙酰半胱氨酸(Parvolex/Acetadote)的方法是持续静脉注射 20 小时(总剂量为 300 毫克/千克)。建议的给药方式是在 15 分钟内输注 150 毫克/千克的负荷剂量,然后在 4 小时内输注 50 毫克/千克;最后 100 毫克/千克在方案的剩余 16 小时内输注。静脉注射乙酰半胱氨酸的优点是可以缩短住院时间,方便医生和患者,而且可以使用活性炭来减少扑热息痛和任何同服药物的吸收,而不必担心口服乙酰半胱氨酸会产生干扰。

实验室检查包括胆红素、谷草转氨酶、谷丙转氨酶和凝血酶原时间(INR)。至少每天重复一次检查。一旦确定发生了潜在的毒性过量,即使血液中的扑热息痛含量已检测不到,乙酰半胱氨酸也会在整个疗程中继续使用。如果出现肝功能衰竭,乙酰半胱氨酸的用量应超过标准剂量,直到肝功能得到改善或患者接受肝移植。

预后

过量服用扑热息痛的死亡率在服药两天后上升,第四天达到最高值,然后逐渐下降。预后较差的患者通常被确定为可能接受肝移植。乙酰胆碱血症是判断死亡率和是否需要移植的最重要的单一指标。据报道,pH值低于7.30的患者在没有移植手术的情况下死亡率高达95%。其他预后不良的指标包括肾功能不全、3 级或更严重的肝性脑病、凝血酶原时间明显升高或凝血酶原时间从第 3 天上升到第 4 天。一项研究表明,V因子水平低于正常的10%表示预后不良(91%的死亡率),而VIII因子与V因子的比值低于30则表示预后良好(100%的存活率)。

预防:除了防止用药过量外,预防肝损伤的一种方法是使用百乐多。百乐多是一种复方片剂,含有 100 毫克蛋氨酸和 500 毫克扑热息痛。加入蛋氨酸是为了确保肝脏中的谷胱甘肽维持在足够的水平,以减少过量服用扑热息痛对肝脏造成的损害。

ref

Regulatory Decision Summary – Acetaminophen Injection". Health Canada. 23 October 2014. Archived from the original on 7 June 2022. Retrieved 7 June 2022.

Working Group of the Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists and Faculty of Pain Medicine (2015). Schug SA, Palmer GM, Scott DA, Halliwell R, Trinca J (eds.). Acute Pain Management: Scientific Evidence (4th ed.). Melbourne: Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists (ANZCA), Faculty of Pain Medicine (FPM). ISBN 978-0-9873236-7-5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 July 2019. Retrieved 28 October 2019.

Forrest JA, Clements JA, Prescott LF (1982). "Clinical pharmacokinetics of paracetamol". Clin Pharmacokinet. 7 (2): 93–107. doi:10.2165/00003088-198207020-00001. PMID 7039926. S2CID 20946160.

"Acetaminophen Pathway (therapeutic doses), Pharmacokinetics". Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 13 January 2016.

Pickering G, Macian N, Libert F, Cardot JM, Coissard S, Perovitch P, Maury M, Dubray C (September 2014). "Buccal acetaminophen provides fast analgesia: two randomized clinical trials in healthy volunteers". Drug Design, Development and Therapy. 8: 1621–1627. doi:10.2147/DDDT.S63476. PMC 4189711. PMID 25302017. In postoperative conditions for acute pain of mild to moderate intensity, the quickest reported time to onset of analgesia with APAP is 8 minutes9 for the iv route and 37 minutes6 for the oral route.

"Codapane Forte Paracetamol and codeine phosphate product information" (PDF). TGA eBusiness Services. Alphapharm Pty Limited. 29 April 2013. Archived from the original on 6 February 2016. Retrieved 10 May 2014.

Karthikeyan M, Glen RC, Bender A (2005). "General Melting Point Prediction Based on a Diverse Compound Data Set and Artificial Neural Networks". Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling. 45 (3): 581–590. doi:10.1021/ci0500132. PMID 15921448.

"melting point data for paracetamol". Lxsrv7.oru.edu. Archived from the original on 30 June 2012. Retrieved 19 March 2011.

Granberg RA, Rasmuson AC (1999). "Solubility of paracetamol in pure solvents". Journal of Chemical & Engineering Data. 44 (6): 1391–95. doi:10.1021/je990124v.

Prescott LF (March 2000). "Paracetamol: past, present, and future". American Journal of Therapeutics. 7 (2): 143–147. doi:10.1097/00045391-200007020-00011. PMID 11319582. S2CID 7754908.

Warwick C (November 2008). "Paracetamol and fever management". J R Soc Promot Health. 128 (6): 320–323. doi:10.1177/1466424008092794. PMID 19058473. S2CID 25702228.

Saragiotto BT, Abdel Shaheed C, Maher CG (December 2019). "Paracetamol for pain in adults". BMJ. 367: l6693. doi:10.1136/bmj.l6693. PMID 31892511. S2CID 209524643.

Chiumello D, Gotti M, Vergani G (April 2017). "Paracetamol in fever in critically ill patients-an update". J Crit Care. 38: 245–252. doi:10.1016/j.jcrc.2016.10.021. PMID 27992852. S2CID 5815020.

de Martino M, Chiarugi A (December 2015). "Recent Advances in Pediatric Use of Oral Paracetamol in Fever and Pain Management". Pain Ther. 4 (2): 149–68. doi:10.1007/s40122-015-0040-z. PMC 4676765. PMID 26518691.

Pierce CA, Voss B (March 2010). "Efficacy and safety of ibuprofen and acetaminophen in children and adults: a meta-analysis and qualitative review". Ann Pharmacother. 44 (3): 489–506. doi:10.1345/aph.1M332. PMID 20150507. S2CID 44669940.

Meremikwu M, Oyo-Ita A (2002). "Paracetamol for treating fever in children". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002 (2): CD003676. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003676. PMC 6532671. PMID 12076499.

Ludwig J, McWhinnie H (May 2019). "Antipyretic drugs in patients with fever and infection: literature review". Br J Nurs. 28 (10): 610–618. doi:10.12968/bjon.2019.28.10.610. PMID 31116598. S2CID 162182092.

Marmura MJ, Silberstein SD, Schwedt TJ (January 2015). "The acute treatment of migraine in adults: the american headache society evidence assessment of migraine pharmacotherapies". Headache. 55 (1): 3–20. doi:10.1111/head.12499. PMID 25600718. S2CID 25576700.

Stephens G, Derry S, Moore RA (June 2016). "Paracetamol (acetaminophen) for acute treatment of episodic tension-type headache in adults". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019 (6): CD011889. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011889.pub2. PMC 6457822. PMID 27306653.

Mayans L, Walling A (February 2018). "Acute Migraine Headache: Treatment Strategies". Am Fam Physician. 97 (4): 243–251. PMID 29671521.

Haag G, Diener HC, May A, Meyer C, Morck H, Straube A, Wessely P, Evers S (April 2011). "Self-medication of migraine and tension-type headache: summary of the evidence-based recommendations of the Deutsche Migräne und Kopfschmerzgesellschaft (DMKG), the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Neurologie (DGN), the Österreichische Kopfschmerzgesellschaft (ÖKSG) and the Schweizerische Kopfwehgesellschaft (SKG)". J Headache Pain. 12 (2): 201–217. doi:10.1007/s10194-010-0266-4. PMC 3075399. PMID 21181425.

Bailey E, Worthington HV, van Wijk A, Yates JM, Coulthard P, Afzal Z (December 2013). "Ibuprofen and/or paracetamol (acetaminophen) for pain relief after surgical removal of lower wisdom teeth". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (12): CD004624. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004624.pub2. PMID 24338830.

Moore PA, Hersh EV (August 2013). "Combining ibuprofen and acetaminophen for acute pain management after third-molar extractions: translating clinical research to dental practice". J Am Dent Assoc. 144 (8): 898–908. doi:10.14219/jada.archive.2013.0207. PMID 23904576.

Machado GC, Maher CG, Ferreira PH, Pinheiro MB, Lin CW, Day RO, et al. (March 2015). "Efficacy and safety of paracetamol for spinal pain and osteoarthritis: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised placebo-controlled trials". BMJ. 350: p225. doi:10.1136/bmj.p225. PMC 4381278. PMID 25828856.

Kolasinski SL, Neogi T, Hochberg MC, Oatis C, Guyatt G, Block J, Callahan L, Copenhaver C, Dodge C, Felson D, Gellar K, Harvey WF, Hawker G, Herzig E, Kwoh CK, Nelson AE, Samuels J, Scanzello C, White D, Wise B, Altman RD, DiRenzo D, Fontanarosa J, Giradi G, Ishimori M, Misra D, Shah AA, Shmagel AK, Thoma LM, Turgunbaev M, Turner AS, Reston J (February 2020). "2019 American College of Rheumatology/Arthritis Foundation Guideline for the Management of Osteoarthritis of the Hand, Hip, and Knee". Arthritis Care & Research. 72 (2): 149–162. doi:10.1002/acr.24131. hdl:2027.42/153772. PMID 31908149. S2CID 210043648.

Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, McLean RM, Forciea MA (April 2017). "Noninvasive Treatments for Acute, Subacute, and Chronic Low Back Pain: A Clinical Practice Guideline From the American College of Physicians". Ann Intern Med. 166 (7): 514–530. doi:10.7326/M16-2367. PMID 28192789. S2CID 207538763.

Saragiotto BT, Machado GC, Ferreira ML, Pinheiro MB, Abdel Shaheed C, Maher CG (June 2016). "Paracetamol for low back pain". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 6 (6): CD012230. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012230. PMC 6353046. PMID 27271789.

Wiffen PJ, Derry S, Moore RA, McNicol ED, Bell RF, Carr DB, McIntyre M, Wee B (July 2017). "Oral paracetamol (acetaminophen) for cancer pain". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 7 (2): CD012637. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012637.pub2. PMC 6369932. PMID 28700092.

Wiffen PJ, Knaggs R, Derry S, Cole P, Phillips T, Moore RA (December 2016). "Paracetamol (acetaminophen) with or without codeine or dihydrocodeine for neuropathic pain in adults". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 12 (5): CD012227. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012227.pub2. PMC 6463878. PMID 28027389.

"Acetaminophen". Health Canada. 11 October 2012. Archived from the original on 3 November 2022. Retrieved 22 September 2022.

Southey ER, Soares-Weiser K, Kleijnen J (September 2009). "Systematic review and meta-analysis of the clinical safety and tolerability of ibuprofen compared with paracetamol in paediatric pain and fever". Current Medical Research and Opinion. 25 (9): 2207–2222. doi:10.1185/03007990903116255. PMID 19606950. S2CID 31653539. Archived from the original on 3 January 2023. Retrieved 2 December 2022.

"Acetaminophen vs Ibuprofen: Which is better?". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 19 February 2023. Retrieved 22 September 2022.

Moore RA, Moore N (July 2016). "Paracetamol and pain: the kiloton problem". European Journal of Hospital Pharmacy. 23 (4): 187–188. doi:10.1136/ejhpharm-2016-000952. PMC 6451482. PMID 31156845.

Conaghan PG, Arden N, Avouac B, Migliore A, Rizzoli R (April 2019). "Safety of Paracetamol in Osteoarthritis: What Does the Literature Say?". Drugs Aging. 36 (Suppl 1): 7–14. doi:10.1007/s40266-019-00658-9. PMC 6509082. PMID 31073920.

Roberts E, Delgado Nunes V, Buckner S, Latchem S, Constanti M, Miller P, Doherty M, Zhang W, Birrell F, Porcheret M, Dziedzic K, Bernstein I, Wise E, Conaghan PG (March 2016). "Paracetamol: not as safe as we thought? A systematic literature review of observational studies". Ann Rheum Dis. 75 (3): 552–9. doi:10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-206914. PMC 4789700. PMID 25732175.

Alchin J, Dhar A, Siddiqui K, Christo PJ (May 2022). "Why paracetamol (acetaminophen) is a suitable first choice for treating mild to moderate acute pain in adults with liver, kidney or cardiovascular disease, gastrointestinal disorders, asthma, or who are older". Current Medical Research and Opinion. 38 (5): 811–825. doi:10.1080/03007995.2022.2049551. PMID 35253560. S2CID 247251679.

Leopoldino AO, Machado GC, Ferreira PH, Pinheiro MB, Day R, McLachlan AJ, Hunter DJ, Ferreira ML (February 2019). "Paracetamol versus placebo for knee and hip osteoarthritis". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2 (8): CD013273. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD013273. PMC 6388567. PMID 30801133.

Choueiri TK, Je Y, Cho E (January 2014). "Analgesic use and the risk of kidney cancer: a meta-analysis of epidemiologic studies". Int J Cancer. 134 (2): 384–96. doi:10.1002/ijc.28093. PMC 3815746. PMID 23400756.

McCrae JC, Morrison EE, MacIntyre IM, Dear JW, Webb DJ (October 2018). "Long-term adverse effects of paracetamol – a review". Br J Clin Pharmacol. 84 (10): 2218–2230. doi:10.1111/bcp.13656. PMC 6138494. PMID 29863746.

MacIntyre IM, Turtle EJ, Farrah TE, Graham C, Dear JW, Webb DJ (February 2022). "Regular Acetaminophen Use and Blood Pressure in People With Hypertension: The PATH-BP Trial". Circulation. 145 (6): 416–423. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.121.056015. PMC 7612370. PMID 35130054.

Bauer AZ, Kriebel D, Herbert MR, Bornehag CG, Swan SH (May 2018). "Prenatal paracetamol exposure and child neurodevelopment: A review". Horm Behav. 101: 125–147. doi:10.1016/j.yhbeh.2018.01.003. PMID 29341895. S2CID 4822468.

Gou X, Wang Y, Tang Y, Qu Y, Tang J, Shi J, Xiao D, Mu D (March 2019). "Association of maternal prenatal acetaminophen use with the risk of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder in offspring: A meta-analysis". Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 53 (3): 195–206. doi:10.1177/0004867418823276. PMID 30654621. S2CID 58575048.

Toda K (October 2017). "Is acetaminophen safe in pregnancy?". Scand J Pain. 17: 445–446. doi:10.1016/j.sjpain.2017.09.007. PMID 28986045. S2CID 205183310.

Black E, Khor KE, Kennedy D, Chutatape A, Sharma S, Vancaillie T, Demirkol A (November 2019). "Medication Use and Pain Management in Pregnancy: A Critical Review". Pain Pract. 19 (8): 875–899. doi:10.1111/papr.12814. PMID 31242344. S2CID 195694287.

"Paracetamol for adults: painkiller to treat aches, pains and fever". National Health Service. Archived from the original on 22 August 2017. Retrieved 22 August 2017.

"What are the recommended maximum daily dosages of acetaminophen in adults and children?". Medscape. Archived from the original on 21 December 2018. Retrieved 19 December 2018.

"Acetaminophen". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 5 June 2016. Retrieved 16 September 2016.

Daly FF, Fountain JS, Murray L, Graudins A, Buckley NA (March 2008). "Guidelines for the management of paracetamol poisoning in Australia and New Zealand—explanation and elaboration. A consensus statement from clinical toxicologists consulting to the Australasian poisons information centres". The Medical Journal of Australia. 188 (5): 296–301. doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.2008.tb01625.x. PMID 18312195. S2CID 9505802.

Hawkins LC, Edwards JN, Dargan PI (2007). "Impact of restricting paracetamol pack sizes on paracetamol poisoning in the United Kingdom: a review of the literature". Drug Saf. 30 (6): 465–79. doi:10.2165/00002018-200730060-00002. PMID 17536874. S2CID 36435353.

Larson AM, Polson J, Fontana RJ, Davern TJ, Lalani E, Hynan LS, et al. (2005). "Acetaminophen-induced acute liver failure: results of a United States multicenter, prospective study". Hepatology. 42 (6): 1364–72. doi:10.1002/hep.20948. PMID 16317692. S2CID 24758491.

Mangus BC, Miller MG (2005). Pharmacology application in athletic training. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: F.A. Davis. p. 39. ISBN 9780803620278. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017. Retrieved 7 September 2017.

Eyers SJ (April 2012). The effect of regular paracetamol on bronchial responsiveness and asthma control in mild to moderate asthma (Ph.D. thesis). University of Otago). Archived from the original on 24 August 2021. Retrieved 24 August 2021.

Roy J (2011). "Paracetamol – the best selling antipyretic analgesic in the world". An introduction to pharmaceutical sciences: production, chemistry, techniques and technology. Oxford: Biohealthcare. p. 270. ISBN 978-1-908818-04-1. Archived from the original on 24 August 2021. Retrieved 24 August 2021.

Aghababian RV (22 October 2010). Essentials of emergency medicine. Jones & Bartlett Publishers. p. 814. ISBN 978-1-4496-1846-9. Archived from the original on 17 August 2016.

World Health Organization (2019). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

Hamilton RJ (2013). Tarascon pocket pharmacopoeia : 2013 classic shirt-pocket edition (27th ed.). Burlington, Massachusetts: Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 12. ISBN 9781449665869. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017.

"The Top 300 of 2020". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on 12 February 2021. Retrieved 7 October 2022.

"Acetaminophen – Drug Usage Statistics". ClinCalc.com. Archived from the original on 12 April 2020. Retrieved 7 October 2022.

"Definition of ACETAMINOPHEN". www.merriam-webster.com. Archived from the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 26 March 2023.

"Definition of PARACETAMOL". www.merriam-webster.com. Archived from the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 26 March 2023.

"A History of Paracetamol, Its Various Uses & How It Affects You". FeverMates. Archived from the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 26 March 2023.

Li S, Yue J, Dong BR, Yang M, Lin X, Wu T (July 2013). "Acetaminophen (paracetamol) for the common cold in adults". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013 (7): CD008800. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008800.pub2. PMC 7389565. PMID 23818046.

de Ridder IR, den Hertog HM, van Gemert HM, Schreuder AH, Ruitenberg A, Maasland EL, Saxena R, van Tuijl JH, Jansen BP, Van den Berg-Vos RM, Vermeij F, Koudstaal PJ, Kappelle LJ, Algra A, van der Worp HB, Dippel DW (April 2017). "PAIS 2 (Paracetamol [Acetaminophen] in Stroke 2): Results of a Randomized, Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial". Stroke. 48 (4): 977–982. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.116.015957. PMID 28289240.

Deen J, von Seidlein L (May 2019). "Paracetamol for dengue fever: no benefit and potential harm?". Lancet Glob Health. 7 (5): e552–e553. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(19)30157-3. PMID 31000122.

Meremikwu M, Oyo-Ita A (2002). "Paracetamol for treating fever in children". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002 (2): CD003676. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003676. PMC 6532671. PMID 12076499.

"Recommendations. Fever in under 5s: assessment and initial management". nice.org.uk. 7 November 2019. Archived from the original on 10 February 2021.

Hashimoto R, Suto M, Tsuji M, Sasaki H, Takehara K, Ishiguro A, Kubota M (April 2021). "Use of antipyretics for preventing febrile seizure recurrence in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Eur J Pediatr. 180 (4): 987–997. doi:10.1007/s00431-020-03845-8. PMID 33125519. S2CID 225994044.

Narayan K, Cooper S, Morphet J, Innes K (August 2017). "Effectiveness of paracetamol versus ibuprofen administration in febrile children: A systematic literature review". J Paediatr Child Health. 53 (8): 800–807. doi:10.1111/jpc.13507. PMID 28437025. S2CID 395470.

Tan E, Braithwaite I, McKinlay CJ, Dalziel SR (October 2020). "Comparison of Acetaminophen (Paracetamol) With Ibuprofen for Treatment of Fever or Pain in Children Younger Than 2 Years: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis". JAMA Netw Open. 3 (10): e2022398. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.22398. PMC 7599455. PMID 33125495.

Sherbash M, Furuya-Kanamori L, Nader JD, Thalib L (March 2020). "Risk of wheezing and asthma exacerbation in children treated with paracetamol versus ibuprofen: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials". BMC Pulm Med. 20 (1): 72. doi:10.1186/s12890-020-1102-5. PMC 7087361. PMID 32293369.

Bertolini A, Ferrari A, Ottani A, Guerzoni S, Tacchi R, Leone S (2006). "Paracetamol: new vistas of an old drug". CNS Drug Rev. 12 (3–4): 250–75. doi:10.1111/j.1527-3458.2006.00250.x. PMC 6506194. PMID 17227290.

Kloppenburg M, Kroon FP, Blanco FJ, Doherty M, Dziedzic KS, Greibrokk E, Haugen IK, Herrero-Beaumont G, Jonsson H, Kjeken I, Maheu E, Ramonda R, Ritt MJ, Smeets W, Smolen JS, Stamm TA, Szekanecz Z, Wittoek R, Carmona L (January 2019). "2018 update of the EULAR recommendations for the management of hand osteoarthritis". Ann Rheum Dis. 78 (1): 16–24. doi:10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-213826. PMID 30154087.

Bruyère O, Honvo G, Veronese N, Arden NK, Branco J, Curtis EM, Al-Daghri NM, Herrero-Beaumont G, Martel-Pelletier J, Pelletier JP, Rannou F, Rizzoli R, Roth R, Uebelhart D, Cooper C, Reginster JY (December 2019). "An updatedTime algorithm recommendation for the management of knee osteoarthritis from the European Society for Clinical and Economic Aspects of Osteoporosis, Osteoarthritis and Musculoskeletal Diseases (ESCEO)". Semin Arthritis Rheum. 49 (3): 337–350. doi:10.1016/j.semarthrit.2019.04.008. hdl:10447/460208. PMID 31126594.

Derry S, Moore RA (2013). "Paracetamol (acetaminophen) with or without an antiemetic for acute migraine headaches in adults". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 4 (4): CD008040. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008040.pub3. PMC 4161111. PMID 23633349.

Diener HC, Gold M, Hagen M (November 2014). "Use of a fixed combination of acetylsalicylic acid, acetaminophen and caffeine compared with acetaminophen alone in episodic tension-type headache: meta-analysis of four randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover studies". J Headache Pain. 15 (1): 76. doi:10.1186/1129-2377-15-76. PMC 4256978. PMID 25406671.

Pergolizzi JV, Magnusson P, LeQuang JA, Gharibo C, Varrassi G (April 2020). "The pharmacological management of dental pain". Expert Opin Pharmacother. 21 (5): 591–601. doi:10.1080/14656566.2020.1718651. PMID 32027199. S2CID 211046298.

Hersh EV, Moore PA, Grosser T, Polomano RC, Farrar JT, Saraghi M, Juska SA, Mitchell CH, Theken KN (July 2020). "Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs and Opioids in Postsurgical Dental Pain". J Dent Res. 99 (7): 777–786. doi:10.1177/0022034520914254. PMC 7313348. PMID 32286125.

Derry CJ, Derry S, Moore RA (June 2013). "Single dose oral ibuprofen plus paracetamol (acetaminophen) for acute postoperative pain". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019 (6): CD010210. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010210.pub2. PMC 6485825. PMID 23794268.

Daniels SE, Atkinson HC, Stanescu I, Frampton C (October 2018). "Analgesic Efficacy of an Acetaminophen/Ibuprofen Fixed-dose Combination in Moderate to Severe Postoperative Dental Pain: A Randomized, Double-blind, Parallel-group, Placebo-controlled Trial". Clin Ther. 40 (10): 1765–1776.e5. doi:10.1016/j.clinthera.2018.08.019. PMID 30245281.

Toms L, Derry S, Moore RA, McQuay HJ (January 2009). "Single dose oral paracetamol (acetaminophen) with codeine for postoperative pain in adults". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009 (1): CD001547. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001547.pub2. PMC 4171965. PMID 19160199.

Allegaert K (2020). "A Critical Review on the Relevance of Paracetamol for Procedural Pain Management in Neonates". Front Pediatr. 8: 89. doi:10.3389/fped.2020.00089. PMC 7093493. PMID 32257982.

Ohlsson A, Shah PS (January 2020). "Paracetamol (acetaminophen) for prevention or treatment of pain in newborns". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 1 (1): CD011219. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011219.pub4. PMC 6984663. PMID 31985830.

Wuytack F, Smith V, Cleary BJ (January 2021). "Oral non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (single dose) for perineal pain in the early postpartum period". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 1 (1): CD011352. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011352.pub3. PMC 8092572. PMID 33427305.

Sin B, Wai M, Tatunchak T, Motov SM (May 2016). "The Use of Intravenous Acetaminophen for Acute Pain in the Emergency Department". Academic Emergency Medicine. 23 (5): 543–53. doi:10.1111/acem.12921. PMID 26824905.

Derry CJ, Derry S, Moore RA (March 2012). Derry S (ed.). "Caffeine as an analgesic adjuvant for acute pain in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 3 (3): CD009281. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009281.pub2. PMID 22419343. S2CID 205199173.

Jasani B, Mitra S, Shah PS (December 2022). "Paracetamol (acetaminophen) for patent ductus arteriosus in preterm or low birth weight infants". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2022 (12): CD010061. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010061.pub5. PMC 6984659. PMID 36519620.

Keaveney A, Peters E, Way B (September 2020). "Effects of acetaminophen on risk taking". Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. 15 (7): 725–732. doi:10.1093/scan/nsaa108. PMC 7511878. PMID 32888031.

"FDA Drug Safety Communication: FDA warns of rare but serious skin reactions with the pain reliever/fever reducer acetaminophen". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 1 August 2013. Archived from the original on 28 October 2019. Retrieved 27 October 2019. Public Domain This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

Lebrun-Vignes B, Guy C, Jean-Pastor MJ, Gras-Champel V, Zenut M (February 2018). "Is acetaminophen associated with a risk of Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis? Analysis of the French Pharmacovigilance Database". Br J Clin Pharmacol. 84 (2): 331–338. doi:10.1111/bcp.13445. PMC 5777438. PMID 28963996.

Kanchanasurakit S, Arsu A, Siriplabpla W, Duangjai A, Saokaew S (March 2020). "Acetaminophen use and risk of renal impairment: A systematic review and meta-analysis". Kidney Res Clin Pract. 39 (1): 81–92. doi:10.23876/j.krcp.19.106. PMC 7105620. PMID 32172553.

Lourido-Cebreiro T, Salgado FJ, Valdes L, Gonzalez-Barcala FJ (January 2017). "The association between paracetamol and asthma is still under debate". The Journal of Asthma (Review). 54 (1): 32–8. doi:10.1080/02770903.2016.1194431. PMID 27575940. S2CID 107851.

Cheelo M, Lodge CJ, Dharmage SC, Simpson JA, Matheson M, Heinrich J, et al. (January 2015). "Paracetamol exposure in pregnancy and early childhood and development of childhood asthma: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Archives of Disease in Childhood. 100 (1): 81–9. doi:10.1136/archdischild-2012-303043. PMID 25429049. S2CID 13520462. Archived from the original on 27 March 2023. Retrieved 28 October 2022.

Eyers S, Weatherall M, Jefferies S, Beasley R (April 2011). "Paracetamol in pregnancy and the risk of wheezing in offspring: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Clinical and Experimental Allergy. 41 (4): 482–9. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2222.2010.03691.x. PMID 21338428. S2CID 205275267.

Fan G, Wang B, Liu C, Li D (2017). "Prenatal paracetamol use and asthma in childhood: A systematic review and meta-analysis". Allergol Immunopathol (Madr). 45 (6): 528–533. doi:10.1016/j.aller.2016.10.014. PMID 28237129.

Masarwa R, Levine H, Gorelik E, Reif S, Perlman A, Matok I (August 2018). "Prenatal Exposure to Acetaminophen and Risk for Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder and Autistic Spectrum Disorder: A Systematic Review, Meta-Analysis, and Meta-Regression Analysis of Cohort Studies". Am J Epidemiol. 187 (8): 1817–1827. doi:10.1093/aje/kwy086. PMID 29688261.

Ji Y, Azuine RE, Zhang Y, Hou W, Hong X, Wang G, Riley A, Pearson C, Zuckerman B, Wang X (February 2020). "Association of Cord Plasma Biomarkers of In Utero Acetaminophen Exposure With Risk of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder and Autism Spectrum Disorder in Childhood". JAMA Psychiatry. 77 (2): 180–189. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.3259. PMC 6822099. PMID 31664451.

"Acetaminophen Information". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 14 November 2017. Archived from the original on 28 October 2019. Retrieved 27 October 2019.Public Domain This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

"Using Acetaminophen and Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs Safely". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 26 February 2018. Archived from the original on 28 October 2019. Retrieved 27 October 2019.Public Domain This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

Amar PJ, Schiff ER (July 2007). "Acetaminophen safety and hepatotoxicity--where do we go from here?". Expert Opinion on Drug Safety. 6 (4): 341–355. doi:10.1517/14740338.6.4.341. PMID 17688378. S2CID 20399748.

Khashab M, Tector AJ, Kwo PY (2007). "Epidemiology of acute liver failure". Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 9 (1): 66–73. doi:10.1007/s11894-008-0023-x. PMID 17335680. S2CID 30068892.

Lee WM (2004). "Acetaminophen and the U.S. Acute Liver Failure Study Group: lowering the risks of hepatic failure". Hepatology. 40 (1): 6–9. doi:10.1002/hep.20293. PMID 15239078. S2CID 15485538.

"Prescription Drug Products Containing Acetaminophen: Actions to Reduce Liver Injury from Unintentional Overdose". regulations.gov. US Food and Drug Administration. 14 January 2011. Archived from the original on 25 September 2012. Retrieved 23 February 2014.Public Domain This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

Yan H (16 January 2014). "FDA: Acetaminophen doses over 325 mg may lead to liver damage". CNN. Archived from the original on 16 February 2014. Retrieved 18 February 2014.

Lee WM (December 2017). "Acetaminophen (APAP) hepatotoxicity—Isn't it time for APAP to go away?". Journal of Hepatology. 67 (6): 1324–1331. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2017.07.005. PMC 5696016. PMID 28734939.

Rumack B, Matthew H (1975). "Acetaminophen poisoning and toxicity". Pediatrics. 55 (6): 871–876. doi:10.1542/peds.55.6.871. PMID 1134886. S2CID 45739342.

"Paracetamol". University of Oxford Centre for Suicide Research. 25 March 2013. Archived from the original on 20 March 2013. Retrieved 20 April 2013.

Mehta S (25 August 2012). "Metabolism of Paracetamol (Acetaminophen), Acetanilide and Phenacetin". PharmaXChange.info. Archived from the original on 28 October 2019. Retrieved 27 October 2019.

"Highlights of Prescribing Information" (PDF). Acetadote. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 February 2014. Retrieved 10 February 2014.

"Paracetamol overdose: new guidance on treatment with intravenous acetylcysteine". Drug Safety Update. September 2012. pp. A1. Archived from the original on 27 October 2012.

"Treating paracetamol overdose with intravenous acetylcysteine: new guidance". GOV.UK. 11 December 2014. Archived from the original on 28 October 2019. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

Nimmo J, Heading RC, Tothill P, Prescott LF (March 1973). "Pharmacological modification of gastric emptying: effects of propantheline and metoclopromide on paracetamol absorption". Br Med J. 1 (5853): 587–9. doi:10.1136/bmj.1.5853.587. PMC 1589913. PMID 4694406.

Toes MJ, Jones AL, Prescott L (2005). "Drug interactions with paracetamol". Am J Ther. 12 (1): 56–66. doi:10.1097/00045391-200501000-00009. PMID 15662293. S2CID 39595470.

Kalsi SS, Wood DM, Waring WS, Dargan PI (2011). "Does cytochrome P450 liver isoenzyme induction increase the risk of liver toxicity after paracetamol overdose?". Open Access Emerg Med. 3: 69–76. doi:10.2147/OAEM.S24962. PMC 4753969. PMID 27147854.

Pinson GM, Beall JW, Kyle JA (October 2013). "A review of warfarin dosing with concurrent acetaminophen therapy". J Pharm Pract. 26 (5): 518–21. doi:10.1177/0897190013488802. PMID 23736105. S2CID 31588052.

Hughes GJ, Patel PN, Saxena N (June 2011). "Effect of acetaminophen on international normalized ratio in patients receiving warfarin therapy". Pharmacotherapy. 31 (6): 591–7. doi:10.1592/phco.31.6.591. PMID 21923443. S2CID 28548170.

Zhang Q, Bal-dit-Sollier C, Drouet L, Simoneau G, Alvarez JC, Pruvot S, Aubourg R, Berge N, Bergmann JF, Mouly S, Mahé I (March 2011). "Interaction between acetaminophen and warfarin in adults receiving long-term oral anticoagulants: a randomized controlled trial". Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 67 (3): 309–14. doi:10.1007/s00228-010-0975-2. PMID 21191575. S2CID 25988269.

Ghanem CI, Pérez MJ, Manautou JE, Mottino AD (July 2016). "Acetaminophen from liver to brain: New insights into drug pharmacological action and toxicity". Pharmacological Research. 109: 119–31. doi:10.1016/j.phrs.2016.02.020. PMC 4912877. PMID 26921661.

Graham GG, Davies MJ, Day RO, Mohamudally A, Scott KF (June 2013). "The modern pharmacology of paracetamol: therapeutic actions, mechanism of action, metabolism, toxicity and recent pharmacological findings". Inflammopharmacology. 21 (3): 201–32. doi:10.1007/s10787-013-0172-x. PMID 23719833. S2CID 11359488.

Sharma CV, Long JH, Shah S, Rahman J, Perrett D, Ayoub SS, Mehta V (2017). "First evidence of the conversion of paracetamol to AM404 in human cerebrospinal fluid". J Pain Res. 10: 2703–2709. doi:10.2147/JPR.S143500. PMC 5716395. PMID 29238213.

Ohashi N, Kohno T (2020). "Analgesic Effect of Acetaminophen: A Review of Known and Novel Mechanisms of Action". Front Pharmacol. 11: 580289. doi:10.3389/fphar.2020.580289. PMC 7734311. PMID 33328986.

Suemaru K, Yoshikawa M, Aso H, Watanabe M (September 2018). "TRPV1 mediates the anticonvulsant effects of acetaminophen in mice". Epilepsy Research. 145: 153–159. doi:10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2018.06.016. PMID 30007240. S2CID 51652230.

Ray S, Salzer I, Kronschläger MT, Boehm S (April 2019). "The paracetamol metabolite N-acetylp-benzoquinone imine reduces excitability in first- and second-order neurons of the pain pathway through actions on KV7 channels". Pain. 160 (4): 954–964. doi:10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001474. PMC 6430418. PMID 30601242.

Prescott LF (October 1980). "Kinetics and metabolism of paracetamol and phenacetin". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 10 (Suppl 2): 291S–298S. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.1980.tb01812.x. PMC 1430174. PMID 7002186.

Graham GG, Davies MJ, Day RO, Mohamudally A, Scott KF (June 2013). "The modern pharmacology of paracetamol: Therapeutic actions, mechanism of action, metabolism, toxicity, and recent pharmacological findings". Inflammopharmacology. 21 (3): 201–232. doi:10.1007/s10787-013-0172-x. PMID 23719833. S2CID 11359488.

Marx J, Walls R, Hockberger R (2013). Rosen's Emergency Medicine – Concepts and Clinical Practice. Elsevier Health Sciences. ISBN 9781455749874.

McGill MR, Jaeschke H (September 2013). "Metabolism and disposition of acetaminophen: recent advances in relation to hepatotoxicity and diagnosis". Pharm Res. 30 (9): 2174–87. doi:10.1007/s11095-013-1007-6. PMC 3709007. PMID 23462933.

Friderichs E, Christoph T, Buschmann H. "Analgesics and Antipyretics". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a02_269.pub2. ISBN 978-3527306732.

"US Patent 2998450". Archived from the original on 14 April 2021.

Bellamy FD, Ou K (January 1984). "Selective reduction of aromatic nitro compounds with stannous chloride in non acidic and non aqueous medium". Tetrahedron Letters. 25 (8): 839–842. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(01)80041-1.

US patent 4524217, Davenport KG, Hilton CB, "Process for producing N-acyl-hydroxy aromatic amines", published 18 June 1985, assigned to Celanese Corporation

Novotny PE, Elser RC (1984). "Indophenol method for acetaminophen in serum examined". Clin. Chem. 30 (6): 884–6. doi:10.1093/clinchem/30.6.884. PMID 6723045.

Cahn A, Hepp P (1886). "Das Antifebrin, ein neues Fiebermittel" [Antifebrin, a new antipyretic]. Centralblatt für klinische Medizin (in German). 7: 561–4. Archived from the original on 1 September 2020. Retrieved 21 February 2019.

Bertolini A, Ferrari A, Ottani A, Guerzoni S, Tacchi R, Leone S (2006). "Paracetamol: New vistas of an old drug". CNS Drug Reviews. 12 (3–4): 250–75. doi:10.1111/j.1527-3458.2006.00250.x. PMC 6506194. PMID 17227290.

Morse HN (1878). "Ueber eine neue Darstellungsmethode der Acetylamidophenole" [On a new method of preparing acetylamidophenol]. Berichte der deutschen chemischen Gesellschaft (in German). 11 (1): 232–233. doi:10.1002/cber.18780110151. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 September 2023. Retrieved 28 December 2023.

Silverman M, Lydecker M, Lee PR (1992). Bad Medicine: The Prescription Drug Industry in the Third World. Stanford University Press. pp. 88–90. ISBN 978-0804716697.

von Mering J (1893). "Beitrage zur Kenntniss der Antipyretica". Ther Monatsch. 7: 577–587.

Sneader W (2005). Drug Discovery: A History. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. p. 439. ISBN 978-0471899808. Archived from the original on 18 August 2016.

Lester D, Greenberg LA, Carroll RP (1947). "The metabolic fate of acetanilid and other aniline derivatives: II. Major metabolites of acetanilid appearing in the blood". J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 90 (1): 68–75. PMID 20241897. Archived from the original on 2 December 2008.

Brodie BB, Axelrod J (1948). "The estimation of acetanilide and its metabolic products, aniline, N-acetyl p-aminophenol and p-aminophenol (free and total conjugated) in biological fluids and tissues". J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 94 (1): 22–28. PMID 18885610.

Brodie BB, Axelrod J (1948). "The fate of acetanilide in man" (PDF). J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 94 (1): 29–38. PMID 18885611. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 September 2008.

Flinn FB, Brodie BB (1948). "The effect on the pain threshold of N-acetyl p-aminophenol, a product derived in the body from acetanilide". J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 94 (1): 76–77. PMID 18885618.

Brodie BB, Axelrod J (September 1949). "The fate of acetophenetidin in man and methods for the estimation of acetophenetidin and its metabolites in biological material". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 97 (1): 58–67. PMID 18140117.

Ameer B, Greenblatt DJ (August 1977). "Acetaminophen". Ann Intern Med. 87 (2): 202–9. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-87-2-202. PMID 329728.

Spooner JB, Harvey JG (1976). "The history and usage of paracetamol". J Int Med Res. 4 (4 Suppl): 1–6. doi:10.1177/14732300760040S403. PMID 799998. S2CID 11289061.

Landau R, Achilladelis B, Scriabine A (1999). Pharmaceutical Innovation: Revolutionizing Human Health. Chemical Heritage Foundation. pp. 248–249. ISBN 978-0-941901-21-5. Archived from the original on 17 August 2016.

"Our Story". McNEIL-PPC, Inc. Archived from the original on 8 March 2014. Retrieved 8 March 2014.

"Medication and Drugs". MedicineNet. 1996–2010. Archived from the original on 22 April 2010. Retrieved 22 April 2010.

"SEC Info – Eastman Kodak Co – '8-K' for 6/30/94". Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 3 March 2016.

"FDA May Restrict Acetaminophen". Webmd. 1 July 2009. Archived from the original on 21 March 2011. Retrieved 19 March 2011.

"FDA limits acetaminophen in prescription combination products; requires liver toxicity warnings" (Press release). U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 13 January 2011. Archived from the original on 15 January 2011. Retrieved 13 January 2011.Public Domain This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

"FDA Drug Safety Communication: Prescription Acetaminophen Products to be Limited to 325 mg Per Dosage Unit; Boxed Warning Will Highlight Potential for Severe Liver Failure". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 13 January 2011. Archived from the original on 18 January 2011. Retrieved 13 January 2011.Public Domain This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

Perrone M (13 January 2011). "FDA orders lowering pain reliever in Vicodin". The Boston Globe. Associated Press. Archived from the original on 2 November 2012. Retrieved 13 January 2011.

Harris G (13 January 2011). "F.D.A. Plans New Limits on Prescription Painkillers". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 9 June 2012. Retrieved 13 January 2011.

"FDA limits acetaminophen in prescription combination products; requires liver toxicity warnings". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (Press release). 15 January 2011. Archived from the original on 15 January 2011. Retrieved 23 February 2014.Public Domain This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

"Liquid paracetamol for children: revised UK dosing instructions introduced" (PDF). Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA). 14 November 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 October 2019. Retrieved 27 October 2019.

"Use Only as Directed". This American Life. Episode 505. Chicago. 20 September 2013. Public Radio International. WBEZ. Archived from the original on 27 September 2013. Retrieved 24 September 2013.

Gerth J, Miller TC (20 September 2013). "Use Only as Directed". ProPublica. Archived from the original on 24 September 2013. Retrieved 24 September 2013.

Miller TC, Gerth J (20 September 2013). "Dose of Confusion". ProPublica. Archived from the original on 24 September 2013. Retrieved 24 September 2013.

Orso D, Federici N, Copetti R, Vetrugno L, Bove T (October 2020). "Infodemic and the spread of fake news in the COVID-19-era". European Journal of Emergency Medicine. 27 (5): 327–328. doi:10.1097/MEJ.0000000000000713. PMC 7202120. PMID 32332201.

Torjesen I (April 2020). "Covid-19: ibuprofen can be used for symptoms, says UK agency, but reasons for change in advice are unclear". BMJ. 369: m1555. doi:10.1136/bmj.m1555. PMID 32303505.

Rinott E, Kozer E, Shapira Y, Bar-Haim A, Youngster I (September 2020). "Ibuprofen use and clinical outcomes in COVID-19 patients". Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 26 (9): 1259.e5–1259.e7. doi:10.1016/j.cmi.2020.06.003. PMC 7289730. PMID 32535147.

Day M (March 2020). "Covid-19: ibuprofen should not be used for managing symptoms, say doctors and scientists". BMJ. 368: m1086. doi:10.1136/bmj.m1086. PMID 32184201.

"Section 1 – Chemical Substances". TGA Approved Terminology for Medicines (PDF). Therapeutic Goods Administration, Department of Health and Ageing, Australian Government. July 1999. p. 97. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 February 2014.

Macintyre P, Rowbotham D, Walker S (26 September 2008). Clinical Pain Management Second Edition: Acute Pain. CRC Press. p. 85. ISBN 978-0-340-94009-9. Archived from the original on 17 August 2016.

"International Non-Proprietary Name for Pharmaceutical Preparations (Recommended List #4)" (PDF). WHO Chronicle. 16 (3): 101–111. March 1962. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 May 2016. Retrieved 21 March 2018.

Gaunt MJ (8 October 2013). "APAP: An Error-Prone Abbreviation". Pharmacy Times. October 2013 Diabetes. 79 (10). Archived from the original on 6 June 2021. Retrieved 6 June 2021.

"Acetaminophen". Physicians' Desk Reference (63rd ed.). Montvale, N.J.: Physicians' Desk Reference. 2009. pp. 1915–1916. ISBN 978-1-56363-703-2. OCLC 276871036.

Nam S. "IV, PO, and PR Acetaminophen: A Quick Comparison". Pharmacy Times. Archived from the original on 24 October 2019. Retrieved 24 October 2019.

"Acetaminophen and Codeine (Professional Patient Advice)". Drugs.com. 29 June 2019. Archived from the original on 20 May 2020. Retrieved 25 February 2020.

"Codeine information hub". Therapeutic Goods Administration, Australian Government. 10 April 2018. Archived from the original on 8 December 2021. Retrieved 9 December 2021.

"Acetaminophen, Caffeine, and Dihydrocodeine (Professional Patient Advice)". Drugs.com. 2 October 2019. Archived from the original on 19 May 2020. Retrieved 25 February 2020.

"Oxycodone and Acetaminophen (Professional Patient Advice)". Drugs.com. 11 November 2019. Archived from the original on 20 May 2020. Retrieved 25 February 2020.

"Hydrocodone and Acetaminophen (Professional Patient Advice)". Drugs.com. 2 January 2020. Archived from the original on 21 May 2020. Retrieved 25 February 2020.

"Propoxyphene and Acetaminophen Tablets". Drugs.com. 21 June 2019. Archived from the original on 20 May 2020. Retrieved 25 February 2020.

"APOHealth Paracetamol Plus Codeine & Calmative". Drugs.com. 3 February 2020. Archived from the original on 25 February 2020. Retrieved 25 February 2020.

Atkinson HC, Stanescu I, Anderson BJ (2014). "Increased Phenylephrine Plasma Levels with Administration of Acetaminophen". New England Journal of Medicine. 370 (12): 1171–1172. doi:10.1056/NEJMc1313942. PMID 24645960.

"Ascorbic acid/Phenylephrine/Paracetamol". NHS Choices. National Health Service. Archived from the original on 26 March 2014. Retrieved 25 March 2014.

"Phenylephrine/Caffeine/Paracetamol dual relief". NHS Choices. National Health Service. Archived from the original on 26 March 2014. Retrieved 25 March 2014.

"Beechams Decongestant Plus With Paracetamol". NHS Choices. National Health Service. Archived from the original on 26 March 2014. Retrieved 25 March 2014.

Senyuva H, Ozden T (2002). "Simultaneous High-Performance Liquid Chromatographic Determination of Paracetamol, Phenylephrine HCl, and Chlorpheniramine Maleate in Pharmaceutical Dosage Forms". Journal of Chromatographic Science. 40 (2): 97–100. doi:10.1093/chromsci/40.2.97. PMID 11881712.

Janin A, Monnet J (2014). "Bioavailability of paracetamol, phenylephrine hydrochloride and guaifenesin in a fixed-combination syrup versus an oral reference product". Journal of International Medical Research. 42 (2): 347–359. doi:10.1177/0300060513503762. PMID 24553480.

"Paracetamol – phenylephrine hydrochloride – guaifenesin". NPS MedicineWise. National Prescribing Service (Australia). Archived from the original on 26 March 2014. Retrieved 25 March 2014.

"Phenylephrine/Guaifenesin/Paracetamol". NHS Choices. National Health Service. Archived from the original on 12 September 2013. Retrieved 25 March 2014.

Allen AL (June 2003). "The diagnosis of acetaminophen toxicosis in a cat". The Canadian Veterinary Journal. 44 (6): 509–10. PMC 340185. PMID 12839249.

Richardson JA (2000). "Management of acetaminophen and ibuprofen toxicoses in dogs and cats" (PDF). Journal of Veterinary Emergency and Critical Care. 10 (4): 285–291. doi:10.1111/j.1476-4431.2000.tb00013.x. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 April 2010.

Maddison JE, Page SW, Church D (2002). Small Animal Clinical Pharmacology. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 260–1. ISBN 978-0702025730.

"Pardale-V Oral Tablets". NOAH Compendium of Data Sheets for Animal Medicines. The National Office of Animal Health (NOAH). 11 November 2010. Archived from the original on 22 November 2008. Retrieved 20 January 2011.

Villar D, Buck WB, Gonzalez JM (June 1998). "Ibuprofen, aspirin and acetaminophen toxicosis and treatment in dogs and cats". Veterinary and Human Toxicology. 40 (3): 156–62. PMID 9610496.

Gwaltney-Brant S, Meadows I (March 2006). "The 10 Most Common Toxicoses in Dogs". Veterinary Medicine: 142–148. Archived from the original on 10 July 2011. Retrieved 28 October 2019.

Dunayer E (2004). "Ibuprofen toxicosis in dogs, cats, and ferrets". Veterinary Medicine: 580–586. Archived from the original on 10 July 2011.

van den Hurk P, Kerkkamp HM (2019). "Phylogenetic origins for severe acetaminophen toxicity in snake species compared to other vertebrate taxa". Comp Biochem Physiol C Toxicol Pharmacol. 215: 18–24. doi:10.1016/j.cbpc.2018.09.003. PMID 30268769. S2CID 52890371.

Johnston J, Savarie P, Primus T, Eisemann J, Hurley J, Kohler D (2002). "Risk assessment of an acetaminophen baiting program for chemical control of brown tree snakes on Guam: evaluation of baits, snake residues, and potential primary and secondary hazards". Environ Sci Technol. 36 (17): 3827–3833. Bibcode:2002EnST...36.3827J. doi:10.1021/es015873n. PMID 12322757.

Lendon B (7 September 2010). "Tylenol-loaded mice dropped from air to control snakes". CNN. Archived from the original on 9 September 2010. Retrieved 7 September 2010.

Richards S (1 May 2012). "It's Raining Mice". The Scientist. Archived from the original on 15 May 2012.

Davanzo R, Bua J, Paloni G, Facchina G (November 2014). "Breastfeeding and migraine drugs". European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology (Review). 70 (11): 1313–1324. doi:10.1007/s00228-014-1748-0. PMID 25217187. S2CID 17144030.

Davies NM (February 1998). "Clinical pharmacokinetics of ibuprofen. The first 30 years". Clinical Pharmacokinetics. 34 (2): 101–154. doi:10.2165/00003088-199834020-00002. PMID 9515184. S2CID 1186212.

"ibuprofen". Archived from the original on 13 January 2015. Retrieved 31 January 2015.

Grosser T, Ricciotti E, FitzGerald GA (August 2017). "The Cardiovascular Pharmacology of Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs". Trends in Pharmacological Sciences (Review). 38 (8): 733–748. doi:10.1016/j.tips.2017.05.008. PMC 5676556. PMID 28651847.

"Brufen Tablets And Syrup" (PDF). Therapeutic Goods Administration. 31 July 2012. Archived from the original on 20 August 2016. Retrieved 8 May 2014.

"Ibuprofen". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 9 September 2017. Retrieved 12 October 2016.

British National Formulary, March 2014–September 2014 (2014 ed.). London: British Medical Association. 2014. pp. 686–688. ISBN 978-0857110862.

"Ibuprofen Pregnancy and Breastfeeding Warnings". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 9 September 2017. Retrieved 22 May 2016.

Kindy D. "The Inventor of Ibuprofen Tested the Drug on His Own Hangover". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 3 July 2021. Stewart Adams and his associate John Nicholson invented a pharmaceutical drug known as 2-(4-isobutylphenyl) propionic acid.

Halford GM, Lordkipanidzé M, Watson SP (2012). "50th anniversary of the discovery of ibuprofen: an interview with Dr Stewart Adams". Platelets. 23 (6): 415–422. doi:10.3109/09537104.2011.632032. PMID 22098129. S2CID 26344532.

"Chemistry in your cupboard: Nurofen". RSC Education. Archived from the original on 5 June 2014.

World Health Organization (2021). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 22nd list (2021). Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/345533. WHO/MHP/HPS/EML/2021.02.

"The Top 300 of 2021". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on 15 January 2024. Retrieved 14 January 2024.

"Ibuprofen. Drug Usage Statistics". ClinCalc. Retrieved 14 January 2024.

"10.1.1 Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs". British National Formulary. Archived from the original on 17 November 2016. Retrieved 13 April 2016.

Griffin G, Tudiver F, Grant WD (April 2002). "Do NSAIDs help in acute or chronic low back pain?". American Family Physician. 65 (7): 1319–1321. PMID 11996413.

Joint Formulary Committee (2013). British National Formulary (BNF) (65 ed.). London, UK: Pharmaceutical Press. pp. 665, 671. ISBN 978-0-85711-084-8.

Rossi, S, ed. (2013). Australian Medicines Handbook (2013 ed.). Adelaide: The Australian Medicines Handbook Unit Trust. ISBN 978-0-9805790-9-3.

Alabed S, Cabello JB, Irving GJ, Qintar M, Burls A (August 2014). "Colchicine for pericarditis" (PDF). The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (Review). 2014 (8): CD010652. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010652.pub2. PMC 10645160. PMID 25164988.

Rostas SE, McPherson CC (2016). "Pharmacotherapy for Patent Ductus Arteriosus: Current Options and Outstanding Questions". Current Pediatric Reviews (Review). 12 (2): 110–119. doi:10.2174/157339631202160506002028. PMID 27197952.

Beaver WT (April 2003). "Review of the analgesic efficacy of ibuprofen". International Journal of Clinical Practice. Supplement (135): 13–17. PMID 12723741.

Seibel K, Schaffler K, Reeh P, Reitmeir P (2004). "Comparison of two different preparations of ibuprofen with regard to the time course of their analgesic effect. A randomised, placebo-controlled, double-blind cross-over study using laser somatosensory evoked potentials obtained from UW-irritated skin in healthy volunteers". Arzneimittel-Forschung. 54 (8): 444–451. doi:10.1055/s-0031-1296997. PMID 15460211. S2CID 592438.

Kyselovič J, Koscova E, Lampert A, Weiser T (June 2020). "A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial of Ibuprofen Lysinate in Comparison to Ibuprofen Acid for Acute Postoperative Dental Pain". Pain and Therapy. 9 (1): 249–259. doi:10.1007/s40122-019-00148-1. PMC 7203382. PMID 31912434.

Fanos V, Antonucci R, Zaffanello M (2010). "Ibuprofen and acute kidney injury in the newborn". The Turkish Journal of Pediatrics. 52 (3): 231–238. PMID 20718179.

Castellsague J, Riera-Guardia N, Calingaert B, Varas-Lorenzo C, Fourrier-Reglat A, Nicotra F, et al. (December 2012). "Individual NSAIDs and upper gastrointestinal complications: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies (the SOS project)". Drug Safety. 35 (12): 1127–46. doi:10.1007/BF03261999. PMC 3714137. PMID 23137151.

Ayres JG, Fleming DM, Whittington RM (May 1987). "Asthma death due to ibuprofen". Lancet. 1 (8541): 1082. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(87)90499-5. PMID 2883408. S2CID 38589434.

Shaikhain TA, Al-Husayni F, Elder K (December 2019). "Ibuprofen-induced Anaphylactic Shock in Adult Saudi Patient". Cureus. 11 (12): e6425. doi:10.7759/cureus.6425. PMC 6970456. PMID 31993263.

Baselt R (2008). Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals in Man (8th ed.). Foster City, USA: Biomedical Publications. pp. 758–761.

"FDA Warns that Using a Type of Pain and Fever Medication in Second Half of Pregnancy Could Lead to Complications". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (Press release). 15 October 2020. Retrieved 15 October 2020. Public Domain This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

"NSAIDs may cause rare kidney problems in unborn babies". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 21 July 2017. Retrieved 15 October 2020. Public Domain This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

Forman JP, Stampfer MJ, Curhan GC (September 2005). "Non-narcotic analgesic dose and risk of incident hypertension in US women". Hypertension. 46 (3): 500–7. doi:10.1161/01.HYP.0000177437.07240.70. PMID 16103274.

Hippisley-Cox J, Coupland C (June 2005). "Risk of myocardial infarction in patients taking cyclo-oxygenase-2 inhibitors or conventional non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: population based nested case-control analysis". BMJ. 330 (7504): 1366. doi:10.1136/bmj.330.7504.1366. PMC 558288. PMID 15947398.

"FDA Drug Safety Communication: FDA strengthens warning that non-aspirin nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) can cause heart attacks or strokes". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 9 July 2015. Archived from the original on 28 October 2019. Retrieved 9 July 2015.

"Ibuprofen- and dexibuprofen-containing medicines". European Medicines Agency (EMA). 22 May 2015. EMA/325007/2015. Archived from the original on 28 October 2019. Retrieved 28 October 2019.

"High-dose ibuprofen (≥2400mg/day): small increase in cardiovascular risk". Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA). 26 June 2015. Archived from the original on 28 October 2019. Retrieved 28 October 2019.

Chan LS (12 June 2014). Hall, R, Vinson, RP, Nunley, JR, Gelfand, JM, Elston, DM (eds.). "Bullous Pemphigoid Clinical Presentation". Medscape Reference. United States: WebMD. Archived from the original on 10 November 2011.

Bergner T, Przybilla B (January 1992). "Photosensitization caused by ibuprofen". Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 26 (1): 114–6. doi:10.1016/0190-9622(92)70018-b. PMID 1531054.

Raksha MP, Marfatia YS (2008). "Clinical study of cutaneous drug eruptions in 200 patients". Indian Journal of Dermatology, Venereology and Leprology. 74 (1): 80. doi:10.4103/0378-6323.38431. hdl:1807/48058. PMID 18193504.

Ward KE, Archambault R, Mersfelder TL (February 2010). "Severe adverse skin reactions to nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs: A review of the literature". American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy. 67 (3): 206–13. doi:10.2146/ajhp080603. PMID 20101062.

Rainsford KD (2012). Ibuprofen: Pharmacology, Therapeutics and Side Effects. London: Springer.

"Ibuprofen". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 6 August 2011.

"Information for Healthcare Professionals: Concomitant Use of Ibuprofen and Aspirin". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). September 2006. Archived from the original on 13 November 2010. Retrieved 22 November 2010.

Lay summary in: "Information about Taking Ibuprofen and Aspirin Together". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 9 September 2019.

Kanabar DJ (February 2017). "A clinical and safety review of paracetamol and ibuprofen in children". Inflammopharmacology. 25 (1): 1–9. doi:10.1007/s10787-016-0302-3. PMC 5306275. PMID 28063133.

McElwee NE, Veltri JC, Bradford DC, Rollins DE (June 1990). "A prospective, population-based study of acute ibuprofen overdose: complications are rare and routine serum levels not warranted". Annals of Emergency Medicine. 19 (6): 657–662. doi:10.1016/S0196-0644(05)82471-0. PMID 2188537.

Vale JA, Meredith TJ (January 1986). "Acute poisoning due to non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Clinical features and management". Medical Toxicology. 1 (1): 12–31. doi:10.1007/BF03259825. PMID 3537613. S2CID 25223555.

Volans G, Hartley V, McCrea S, Monaghan J (March–April 2003). "Non-opioid analgesic poisoning". Clinical Medicine. 3 (2): 119–123. doi:10.7861/clinmedicine.3-2-119. PMC 4952728. PMID 12737366.

Seifert SA, Bronstein AC, McGuire T (2000). "Massive ibuprofen ingestion with survival". Journal of Toxicology. Clinical Toxicology. 38 (1): 55–57. doi:10.1081/clt-100100917. PMID 10696926. S2CID 38588541.

American Academy Of Clinical Toxico (2004). "Position paper: Ipecac syrup". Journal of Toxicology. Clinical Toxicology. 42 (2): 133–143. doi:10.1081/CLT-120037421. PMID 15214617. S2CID 218865551.

Hall AH, Smolinske SC, Conrad FL, Wruk KM, Kulig KW, Dwelle TL, et al. (November 1986). "Ibuprofen overdose: 126 cases". Annals of Emergency Medicine. 15 (11): 1308–1313. doi:10.1016/S0196-0644(86)80617-5. PMID 3777588.

Verma P, Clark CA, Spitzer KA, Laskin CA, Ray J, Koren G (July 2012). "Use of non-aspirin NSAIDs during pregnancy may increase the risk of spontaneous abortion". Evidence-Based Nursing. 15 (3): 76–77. doi:10.1136/ebnurs-2011-100439. PMID 22411163. S2CID 28521248.

Daniel S, Koren G, Lunenfeld E, Bilenko N, Ratzon R, Levy A (March 2014). "Fetal exposure to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and spontaneous abortions". CMAJ. 186 (5): E177–E182. doi:10.1503/cmaj.130605. PMC 3956584. PMID 24491470.

Rao P, Knaus EE (September 2008). "Evolution of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs): cyclooxygenase (COX) inhibition and beyond". Journal of Pharmacy & Pharmaceutical Sciences. 11 (2): 81s–110s. doi:10.18433/J3T886. PMID 19203472.

Kakuta H, Zheng X, Oda H, Harada S, Sugimoto Y, Sasaki K, et al. (April 2008). "Cyclooxygenase-1-selective inhibitors are attractive candidates for analgesics that do not cause gastric damage. design and in vitro/in vivo evaluation of a benzamide-type cyclooxygenase-1 selective inhibitor". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 51 (8): 2400–2411. doi:10.1021/jm701191z. PMID 18363350.

"Ibuprofen". DrugBank. Archived from the original on 21 July 2014. Retrieved 24 July 2014.

Kopp MA, Liebscher T, Niedeggen A, Laufer S, Brommer B, Jungehulsing GJ, et al. (July 2012). "Small-molecule-induced Rho-inhibition: NSAIDs after spinal cord injury". Cell and Tissue Research. 349 (1): 119–132. doi:10.1007/s00441-012-1334-7. PMC 3744771. PMID 22350947.

Luo M, Li YQ, Lu YF, Wu Y, Liu R, Zheng YR, et al. (November 2020). "Exploring the potential of RhoA inhibitors to improve exercise-recoverable spinal cord injury: A systematic review and meta-analysis". Journal of Chemical Neuroanatomy. 111: 101879. doi:10.1016/j.jchemneu.2020.101879. PMID 33197553.

Nakagita T, Taketani C, Narukawa M, Hirokawa T, Kobayashi T, Misaka T (7 November 2020). "Ibuprofen, a Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drug, is a Potent Inhibitor of the Human Sweet Taste Receptor". Chemical Senses. 45 (8): 667–673. doi:10.1093/chemse/bjaa057. ISSN 0379-864X.

Bushra R, Aslam N (July 2010). "An overview of clinical pharmacology of Ibuprofen". Oman Medical Journal. 25 (3): 155–161. doi:10.5001/omj.2010.49. PMC 3191627. PMID 22043330.

Brayfield, A, ed. (14 January 2014). "Ibuprofen". Martindale: The Complete Drug Reference. London, UK: Pharmaceutical Press. Retrieved 26 June 2014.

"The Synthesis of Ibuprofen". Royal Society of Chemistry. Retrieved 22 November 2018.

"The Ibuprofen Revolution". Science. Retrieved 17 March 2023.

Murphy MA (1 July 2018). "Early Industrial Roots of Green Chemistry and the history of the BHC Ibuprofen process invention and its Quality connection". Foundations of Chemistry. 20 (2): 121–165. doi:10.1007/s10698-017-9300-9. ISSN 1572-8463. S2CID 254510261.

Grimaldi F, Tran NN, Sarafraz MM, Lettieri P, Morales-Gonzalez OM, Hessel V (4 October 2021). "Life Cycle Assessment of an Enzymatic Ibuprofen Production Process with Automatic Recycling and Purification" (PDF). ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering. 9 (39): 13135–13150. doi:10.1021/acssuschemeng.1c02309. ISSN 2168-0485.

US4981995A, Elango V, Murphy MA, Smith BL, Davenport KG, "Method for producing ibuprofen", issued 1991-01-01

Jayasree S, Seayad A, Chaudhari RV (1999). "Highly active supported palladium catalyst for the regioselective synthesis of 2-arylpropionic acids by carbonylation". Chemical Communications (12): 1067–1068. doi:10.1039/a902541c. hdl:1808/18897.

Tracy TS, Hall SD (March–April 1992). "Metabolic inversion of (R)-ibuprofen. Epimerization and hydrolysis of ibuprofenyl-coenzyme A". Drug Metabolism and Disposition. 20 (2): 322–327. PMID 1352228.

Chen CS, Shieh WR, Lu PH, Harriman S, Chen CY (July 1991). "Metabolic stereoisomeric inversion of ibuprofen in mammals". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Protein Structure and Molecular Enzymology. 1078 (3): 411–417. doi:10.1016/0167-4838(91)90164-U. PMID 1859831.

Reichel C, Brugger R, Bang H, Geisslinger G, Brune K (April 1997). "Molecular cloning and expression of a 2-arylpropionyl-coenzyme A epimerase: a key enzyme in the inversion metabolism of ibuprofen" (PDF). Molecular Pharmacology. 51 (4): 576–582. doi:10.1124/mol.51.4.576. PMID 9106621. S2CID 835701. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 March 2019.

Caldwell J, Hutt AJ, Fournel-Gigleux S (January 1988). "The metabolic chiral inversion and dispositional enantioselectivity of the 2-arylpropionic acids and their biological consequences". Biochemical Pharmacology. 37 (1): 105–114. doi:10.1016/0006-2952(88)90762-9. PMID 3276314.

Simonyi M (1984). "On chiral drug action". Medicinal Research Reviews. 4 (3): 359–413. doi:10.1002/med.2610040304. PMID 6087043. S2CID 38829275.

Hutt AJ, Caldwell J (November 1983). "The metabolic chiral inversion of 2-arylpropionic acids--a novel route with pharmacological consequences". The Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology. 35 (11): 693–704. doi:10.1111/j.2042-7158.1983.tb02874.x. PMID 6139449. S2CID 40669413.

Adams SS (April 1992). "The propionic acids: a personal perspective". Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 32 (4): 317–323. doi:10.1002/j.1552-4604.1992.tb03842.x. PMID 1569234. S2CID 22857259.

Rainsford KD (April 2003). "Discovery, mechanisms of action and safety of ibuprofen". International Journal of Clinical Practice. Supplement (135): 3–8. PMID 12723739.

Lambert V (8 October 2007). "Dr Stewart Adams: 'I tested ibuprofen on my hangover'". The Daily Telegraph. UK. Archived from the original on 18 November 2015. Retrieved 23 October 2015.(Subscription required.)

"A brief History of Ibuprofen". Pharmaceutical Journal. 27 July 2017. Retrieved 20 February 2022.

"Boots Hidden Heroes - Honoring Dr Stewart Adams". Boots Newsroom Features. Boots. Retrieved 20 February 2022.

"Chemical landmark plaque honours scientific discovery past and future" (Press release). Royal Society of Chemistry (RSC). 21 November 2013.

"Written submission to the NDAC meeting on risks of NSAIDs presented by the International Ibuprofen Foundation". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). August 2002. Archived from the original on 15 August 2013. Retrieved 20 March 2014.

"New Drug Application (NDA): 017463". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Archived from the original on 28 October 2019. Retrieved 28 October 2019.