开空调有利于减脂

开空调对减脂是有利的,这有大量证据。

有人仅仅把原因归结为运动量和总热量,认为开空调能让人保持持续运动,消耗更多的热量。

这是肤浅和错误的,因为 即便在同样的运动量下、同样的总热量消耗下,凉爽的温度也会消耗更多的脂肪。

一、高温阻碍脂肪氧化,影响体能

『脂肪燃烧』用正规一点的话来说叫做『脂肪氧化』,大家再看到这几个字的时候不要觉得疑惑和陌生,氧化和燃烧的含义比较类似。

提升脂肪氧化水平的因素很多,比如运动。运动强度是影响脂肪氧化的主要因素之一 [1] :中等强度(最大摄氧量的40%至60%)时通常会获得最大脂肪氧化速率 [2] 。其他因素,如运动持续时间、运动前进食 [3] 、咖啡因 [4] 和其他一些物质 [5] 的使用,甚至性别 [6] ,也都能一定程度改变运动期间的脂肪氧化。

还有个影响脂肪氧化的重要因素很少被人关注,那就是温度——较高的环境温度下进行有氧和耐力运动,会削弱预期的减脂效果。

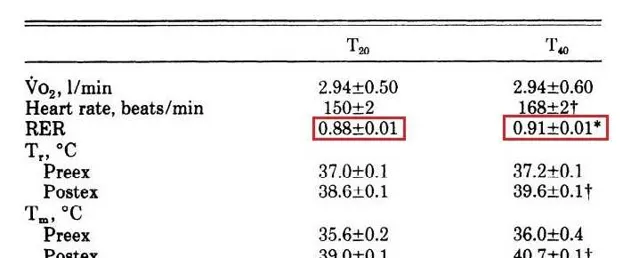

第一个典型研究是Febbraio等人1994年的 [7] 。

Febbraio等人对具有耐力训练经验的男性研究发现,进行70%最大摄氧量的40分钟自行车运动,在高温下进行,相对低温下进行来说,脂肪氧化减少25%,糖类氧化增加31%;对于减脂来说,这就比较糟糕了。

在该研究中,他们用的是一种叫呼吸交换率(RER)的技术进行测量:RER=VCO2/VO2,也就是呼出的二氧化碳和消耗氧气的之比。

因为动物同时氧化脂肪和碳水来供能 [8] [9] [10] ,并且根据体内氧化脂肪和碳水的比例不同,所吸入的氧气和呼出的二氧化碳的比例也不同 [11] [12] [13] 。如果只氧化脂肪供能,二氧化碳与氧气消耗之比为0.7;如果只氧化碳水供能,二氧化碳与氧气消耗之比为1。

因此,呼吸交换率低,氧化脂肪供能多,氧气的消耗也相对多。

从文献原文的截图可见,20°C运动的呼吸交换率平均值是0.88,40°C运动的呼吸交换率则是0.91,升高的呼吸交换率意味着在高温下运动,人体碳水供能增加,脂肪氧化减少 [7] 。

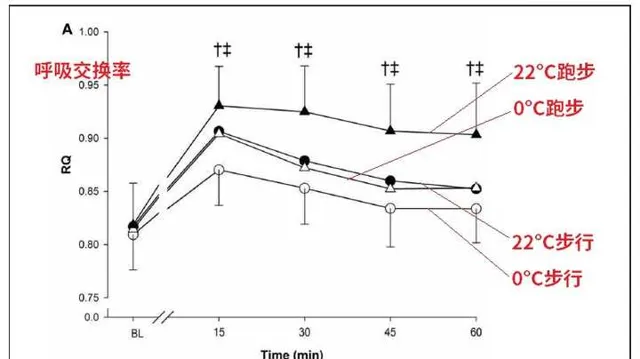

第二个典型研究是Gagnon等人2013年的 [13] 。

Gagnon等人招募了10个健康、经常活动的受试者,让他们穿着单薄的衣服,分别在0或者22°C下,进行50%或者70%最大摄氧量的有氧活动。结果并不出人意外,受试者们的呼吸交换率,在低温下更低——也就是说,低温下做有氧,脂肪氧化占比更大,对糖类的利用相对少些。

也就是说,低温状态运动增加了脂肪氧化。

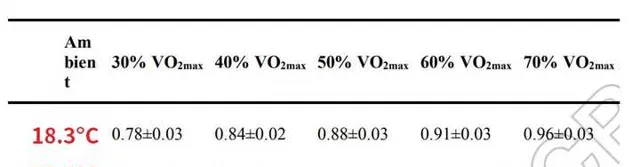

第三个典型研究是Carlos等人2020年的 [14] 。

Carlos等人研究了12名健康年轻人,让他们分别在两种温度(18.3ºC或36.3ºC)执行多种不同强度的有氧运动(30%—70%最大心率)。

根据原文截图,在18.3ºC下,5种强度的有氧运动呼吸交换率平均值从0.78到0.96;在36.3ºC下,5种强度的有氧运动呼吸交换率平均值从0.81到0.99,这说明温度越高,呼吸交换律越高,脂肪氧化占比越少。

注意,炎热环境下运动,身体消耗的总能量也更少,不利于减脂。

Carlos等人2021年招募了12名年轻健康的受试者在18.3或者36.3°C下进行坡道自行车测试 [15] ,结果发现相对于凉爽环境,炎热环境导致总热量消耗下降。

(1)在50%最大心率的运动中,18.3ºC的凉爽温度下运动时每分钟平均消耗10.47大卡,36.3ºC的炎热温度下运动运动时每分钟平均消耗10.42大卡;

(2)在70%最大心率的运动中,18.3ºC的凉爽温度下运动时每分钟平均消耗15.15大卡,36.3ºC的炎热温度下运动运动时每分钟平均消耗14.79大卡。

此外,这种规律在动物中也存在。

当环境温度从35ºC提高到40ºC,大鼠的肌肉中脂肪酸氧化减少、更偏向使用碳水化合物 [16] ;水温会显著的影响鱼类的长链脂肪酸代谢 [17] [18] [19] 和身体脂肪沉淀 [20] [21] [22] [23] [24] 。

总之,开空调的健身房才是好健身房,减脂应该在凉爽的条件下进行,这不仅仅关系到中暑,也关系到脂肪氧化 [25] ,关系到人体能量代谢的改变。

二、温度对脂解激素有重要影响

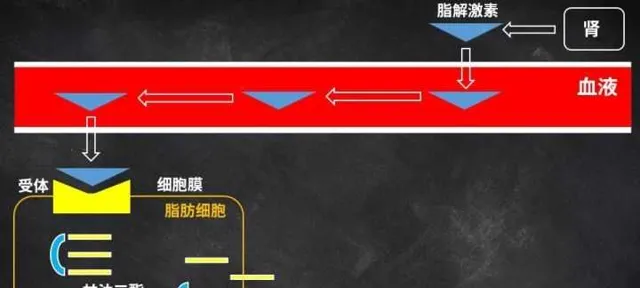

脂解激素,顾名思义,就是让脂肪分解的激素。

人体内的脂肪主要是甘油三酯 [26] [27] ,但它比较大,是一个甘油骨架和三个脂肪酸链组成的 [28] [29] ,没法直接运出脂肪细胞,所以人体需要一些激素,激活细胞内的酶 [30] [31] [32] ,把脂肪酸从甘油骨架上切割下来 [33] [34] [35] ,再在各类运载蛋白 [36] [37] 的帮助下从血液 [38] 输送到各器官细胞内的线粒体中氧化 [39] [40] 。

这些激活脂肪分解的激素,就是『脂解激素』 [41] [42] ,比如肾上腺素 [43] 和它的衍生物去甲肾上腺素 [44] 。

脂解激素被分泌后,从血液到达脂肪细胞,与脂肪细胞表面的受体结合 [45] [46] [47] [48] ,引发一系列反应 [49] [50] [51] [52] ,让脂肪细胞中的脂肪酸被释放出来 [53] [54] ,供肌肉和其他器官使用,这个过程就叫脂解。

本文谈论的应该是夏天是否开空调,在这个背景下,温度能影响『脂解激素』:去甲肾上腺素的合成和释放,从而影响脂肪分解和氧化 [55] ;『脂解激素』在相对低的温度下容易被激发释放。

1973年,Galbo等人发现,人类在21℃水中游泳1小时,肾上腺素和去甲肾上腺素的水平比27℃的水中游泳时更高 [56] ;

2002年,Steven等人通过向健康男性静脉内大量注射4℃冷盐水的方式,使他们的核心温度下降0.7℃,结果他们的血浆去甲肾上腺素增加增加220%;如果进一步注射,受试者们的核心温度进一步降低达到1℃,则受试者血浆去甲肾上腺素浓度增加230%,血浆肾上腺素浓度增加68% [57] 。

1997年,Frank等人进行了类似的实验,通过向人类静脉注射大量4℃冷盐水的方式降低人类的核心温度,发现当核心温度降低0.7℃时,受试者们的平均血浆去甲肾上腺素浓度增加400%,全身耗氧量增加30%;当核心温度降低1.3摄氏度时,平均去甲肾上腺素浓度增加700%,全身耗氧量增加112% [58] 。

这些数据都说明,较低的温度可以有利于脂解激素的释放,从而促进脂解和脂肪氧化 [59] 。

注意,Frank等人的研究中 [58] ,受试者们的核心温度下降,脂解激素增加,伴随一个重要现象:『耗氧量增加』。原因是呼吸交换率计算时,氧气是分母,二氧化碳是分子,耗氧量增加意味着更低的呼吸交换率,更多的脂肪氧化和更少的糖酵解。

三、高温减少脂肪组织的血流量,从而抑制脂肪分解

对于减脂来说,血流量是个极为重要的因素。

我们就以之前已经论证过的『局部减脂』来说,有大量证据表明,不管是运动、节食,还是运动结合节食,结果都是内脏脂肪优先分解,内脏脂肪的分解明显多于皮下脂肪 [60] [61] [62] [63] [64] [65] [66] [67] [68] [69] [70] [71] [72] [73] [73] [74] [75] [76] [77] [78] [79] [80] [81] [82] [83] [84] [85] 。这是因为内脏脂肪的代谢流动性高于皮下脂肪,内脏脂肪对脂解激素更敏感 [86] [87] [88] [89] 。

并且就算这个『局部性』指的不是『内脏脂肪和皮下脂肪的分别』,而是『练哪瘦哪』,也有一些证据支持它成立 [90] [91] [92] [93] [94] [95] [96] 。

注意,『局部减脂』就是建立在血流量基础上的。

因为脂肪细胞并不仅仅是能量的容器,它们也是进行积极代谢的细胞,它们非常活跃,富含神经和结缔组织,而且几乎每个脂肪细胞都配有毛细血管 [97] [98] [99] ,脂肪的运输和代谢受血液流动影响 [100] [101] ;

运动能减肥,在一定程度上也是因为运动促进全身血管生长的血管生成 [102] ,从而改善脂肪组织的血流量;耐力和有氧运动可以诱导人类 [103] 和动物 [104] 皮下脂肪组织中血管生成因子(VEGF)的表达上调 [105] ,从而增加脂肪组织的毛细血管生成,起到预防、对抗肥胖的作用;

对健康受试者测试发现,运动腿脂肪组织的血流量显著高于休息腿脂肪组织的血流量 [106] ;权威期刊【应用生理学】表明,在运动期间,运动腿脂肪组织血流量从每100g肌肉1毫升/每分钟,猛增到到最高每100g肌肉4.9毫升/分钟,提高了接近5倍;与此同时,休息腿脂肪组织血流量基本保持不变 [107] ;

更重要的是,主要的脂解激素,如肾上腺素和去甲肾上腺素 [108] [109] ,是通过血液运输到脂肪细胞 [110] 的;并且脂解激素也反过来增加脂肪组织的血流量,从而促进脂肪分解。例如,给大鼠注射去甲肾上腺素后,大鼠脂肪组织的血流量从2%增加到15.5% [111] 。

与此相对的是,肥胖与脂肪组织血流下降、毛细血管稀疏之间存在密切关系:

重点: 较高的环境温度削减脂肪组织血流量,从而抑制脂肪分解

其实在正常而非炎热的环境下运动时,脂肪组织跟肌肉组织一样,血流量是明显增加的。例如,4小时自行车运动后,皮下脂肪和肾周围脂肪的血流量增加了400%和700% [126] ;狗在长时间运动后皮下脂肪的血流量增加了2倍,相应导致脂解增加,游离脂肪酸和甘油水平增加 [127] 。

并且, 流向肌肉的血流量,跟流向脂肪组织的血流量之间具有一定程度的同步性,例如伸膝训练使股四头肌的温度增加了2 ℃ [128] ,也导致肌肉附近的脂肪组织的温度和血流量提高 [128] 。

在炎热环境下,脂肪组织的血流量减少,皮肤获得的血流量增加 。在33℃的高温环境饲养时,仔猪流向脂肪组织的血流减少42%,流向外皮肤的血流增加44% [129] ;而在寒冷环境中,1-5日龄的仔猪骨骼肌血流量提升最高达41%,皮肤血流量减少24% [130] 。

因为皮肤是人和高等动物排汗和调节体温的重要器官,在高温下皮肤会与脂肪组织抢夺血流量 。众所周知,皮肤上存在各类感受温度的传感器 [131] [132] ,能通过多种路径 [133] [134] [135] 感受炎热的外部环境,将『气温太高』的信号传递到神经系统;然后在神经系统信号的调节下 [136] [137] ,皮肤的毛细血管舒张 [137] ,血流量增加 [138] [139] [140] 来散热,从而调节我们身体的温度 [141] 。

炎热导致皮肤血流量上升,脂肪组织血流量下降,它们彼此争夺、竞争血流量,从而削减了脂肪组织获得的脂解激素 [41] [42] [43] [44] 的数量,导致脂肪氧化减少 [7] [13] [14] [15] [16] ,减脂效果下降。

结 论

减脂,应当选择凉爽的气温环境,夏天温度升高一定要开空调,这样减脂效率更高。

而且闷热/炎热的环境除了不利于脂肪分解,也容易造成脱水、离子损失甚至是中暑,不管对舒适性、运动效果、减脂、安全性都存在负面影响。

扩展阅读

肉崽:力训研究所课程介绍

肉崽:拉伸可以提高跑步成绩,避免运动损伤吗?

肉崽:即便能量充足,低碳水也很难增肌

肉崽:为什么碳水和糖才是长胖元凶,明明脂肪热量更高啊?

肉崽:局部减脂是如何被确认的

肉崽:练哪瘦哪可能存在,前提是方法正确

肉崽:健身增肌的原理是什么?

肉崽:水果中的果糖会让人长胖吗?

肉崽:为什么减脂容易掉肌肉?

肉崽:不健身直接吃蛋白粉会怎么样

参考

- ^ Randell, R. K., Rollo, I., Roberts, T. J., Dalrymple, K. J., Jeukendrup, A. E., & Carter, J. M. (2017). Maximal Fat Oxidation Rates in an Athletic Population. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 49(1), 133–140.

- ^ Achten, J., Gleeson, M., & Jeukendrup, A. E. (2002). Determination of the exercise intensity that elicits maximal fat oxidation. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise.

- ^ Achten, J., Venables, M. C., & Jeukendrup, A. E. (2003). Fat oxidation rates are higher during running compared with cycling over a wide range of intensities. Metabolism: Clinical and Experimental.

- ^ Gutiérrez-Hellín, J., & Del Coso, J. (2018). Effects of p-Synephrine and Caffeine Ingestion on Substrate Oxidation during Exercise. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 50(9), 1899–1906.

- ^ Gutiérrez-Hellín, J., & Del Coso, J. (2016). Acute p-synephrine ingestion increases fat oxidation rate during exercise. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology.

- ^ Venables, M. C., Achten, J., & Jeukendrup, A. E. (2005). Determinants of fat oxidation during exercise in healthy men and women: A cross-pal study. Journal of Applied Physiology.

- ^ a b c Febbraio, M. A., Snow, R. J., Stathis, C. G., Hargreaves, M., & Carey, M. F. (1994). Effect of heat stress on muscle energy metabolism during exercise. Journal of Applied Physiology, 77(6), 2827–2831.

- ^ Wilson DF. Regulation of cellular metabolism: programming and maintaining metabolic homeostasis. J Appl Physiol. (2013):15:1583–8.

- ^ Weekes CE. Controversies in the determination of energy requirements. Proc Nutr Soc. (2007) 66:367–77.

- ^ Lowell BB, Spiegelman BM. Towards a molecular understanding of adaptive thermogenesis. Nature (2000) 404:652–60.

- ^ Kenny GP, Notley SR, Gagnon D. Direct calorimetry: a brief historical review of its use in the study of human metabolism and thermoregulation. Eur J Appl Physiol. (2017) 117:1765–85.

- ^ Poncet S, Dahlberg L. The legacy of henri victor regnault in the arts and sciences. Intl J Arts Sci. (2011) 4:377–400.

- ^ a b c Dominique D. Gagnon,1,* Hannu Rintamäki,2,3 Sheila S. Gagnon,4 Stephen S. Cheung,5 Karl-Heinz Herzig,2,6 Katja Porvari,7 and Heikki Kyröläinen1.Cold exposure enhances fat utilization but not non-esterified fatty acids, glycerol or catecholamines availability during submaximal walking and running.Front Physiol. 2013; 4: 99.

- ^ a b Gagnon, D. D., Perrier, L., Dorman, S. C., Oddson, B., Larivière, C., & Serresse, O. (2020). Ambient temperature influences metabolic substrate oxidation curves during running and cycling in healthy men. European Journal of Sport Science, 20(1), 90–99.

- ^ a b Carlos Ruíz-Moreno , Jorge Gutiérrez-Hellín , Jaime González-García ,Verónica Giráldez-Costas , Diego Brito de Souza & Juan Del Coso (2020): Effect of ambient temperature on fat oxidation during an incremental cycling exercise test, European Journal of Sport Science,

- ^ a b Pierre-Emmanuel Tardo-Dino 1 2 3, Julianne Touron 1, Stéphane Baugé 1, Stéphanie Bourdon 1, Nathalie Koulmann 1 2 3, Alexandra Malgoyre 1.The effect of a physiological increase in temperature on mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation in rat myofibers.J Appl Physiol (1985). 2019 Aug 1;127(2):312-319.

- ^ Calder PC. n−3 Polyunsaturated fatty acids, inflammation, and inflammatory diseases. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2006;83(6):S1505–19S.

- ^ ocher DR. Fatty acid requirements in ontogeny of marine and freshwater fish. Aquaculture Research. 2010;41(5):717–32.

- ^ Hazel JR. Effects of temperature on the structure and metabolism of cell membranes in fish. The American journal of physiology. 1984;246(4 Pt 2):R460–70. Epub

- ^ Jobling M, Bendiksen EÅ. Dietary lipids and temperature interact to influence tissue fatty acid compositions of Atlantic salmon, Salmo salar L., parr. Aquaculture Research. 2003;34(15):1423–41

- ^ Hazel JR. Influence of thermal acclimation on membrane lipid composition of rainbow trout liver. The American journal of physiology. 1979;236(1):R91–101. Epub

- ^ Wodtke E. Lipid adaptation in liver mitochondrial membranes of carp acclimated to different environmental temperatures: phospholipid composition, fatty acid pattern and cholesterol content. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 1978;529(2):280–91. Epub

- ^ Bendiksen EÅ, Jobling M. Effects of temperature and feed composition on essential fatty acid (n-3 and n-6) retention in Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar L.) parr. Fish Physiol Biochem. 2003;29(2):133–40.

- ^ Arts MT, Palmer ME, Skiftesvik AB, Jokinen IE, Browman HI. UVB radiation variably affects n-3 fatty acids but elevated temperature reduces n-3 fatty acids in juvenile Atlantic Salmon (Salmo salar). Lipids. 2012;47(12):1181–92.

- ^ Hurley B., Haymes E. M. (1982). The effects of rest and exercise in the cold on substrate mobilization and utilization. Aviat. Space Environ. Med. 53, 1193–1197

- ^ Reshef L., Olswang Y., Cassuto H., Blum B., Croniger C.M., Kalhan S.C. Glyceroneogenesis and the triglyceride/fatty acid cycle. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2003;278(33):30413–30416.

- ^ D. Zweytick, K. Athenstaedt, G. Daum, Intracellular lipid particles of eukaryotic cells, BBA-Rev Biomembranes. 1469(2) (2000) 101-120.

- ^ aughan, M. J. (1962) J. Biol. Chem. 237, 3354–3358

- ^ Viecili P.R.N., da Silva B., Hirsch G.E., Porto F.G., Parisi M.M., Castanho A.R. Triglycerides revisited to the serial. Advances in Clinical Chemistry. 2017;80:1–44.

- ^ Jocken J.W., Blaak E.E. Catecholamine-induced lipolysis in adipose tissue and skeletal muscle in obesity. Physiol. Behav. 2008;94:219–230.

- ^ Holm C., Osterlund T., Laurell H., Contreras J.A. Molecular mechanisms regulating hormone-sensitive lipase and lipolysis. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2000;20:365–393.

- ^ Shen W.J., Patel S., Natu V., Kraemer F.B. Mutational analysis of structural features of rat hormone-sensitive lipase. Biochemistry. 1998;37:8973–8979.

- ^ Zechner R, Kienesberger PC, Haemmerle G, Zimmermann R, Lass A 2009. Adipose triglyceride lipase and the lipolytic catabolism of cellular fat stores. J Lipid Res 50: 3–21

- ^ Zimmermann R, Strauss JG, Haemmerle G, Schoiswohl G, Birner-Gruenberger R, Riederer M, Lass A, Neuberger G, Eisenhaber F, Hermetter A, et al. 2004. Fat mobilization in adipose tissue is promoted by adipose triglyceride lipase. Science 306: 1383–1386

- ^ Haemmerle G, Zimmermann R, Hayn M, Theussl C, Waeg G, Wagner E, Sattler W, Magin TM, Wagner EF, Zechner R 2002. Hormone-sensitive lipase deficiency in mice causes diglyceride accumulation in adipose tissue, muscle, and testis. J Biol Chem 277: 4806–4815

- ^ Ranallo R.F., Rhodes E.C. Lipid metabolism during exercise. Sports Med. 1998;26:29–42.

- ^ Campbell J, Martucci AD, Green GR. Plasma albumin as an acceptor of free fatty acids. Biochem J. 1964;93:183–189.

- ^ Miller N.E. HDL metabolism and its role in lipid transport. Eur. Heart J. 1990;11:1–3.

- ^ Jeukendrup AE. Regulation of fat metabolism in skeletal muscle. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2002;967:217–235.

- ^ Harasim E., Kalinowska A., Chabowski A., Stepek T. The role of fatty-acid transport proteins (FAT/CD36, FABPpm, FATP) in lipid metabolism in skeletal muscles. Postepy Higieny Medycyny Doswiadczalnej. 2008;62:433–441.

- ^ a b eters S. J., Dyck D. J., Bonen A., Spriet L. L. Effects of epinephrine on lipid metabolism in resting skeletal muscle. The American Journal of Physiology. 1998;275(2 Part 1):E300–E309.

- ^ a b Dyck D. J., Bonen A. Muscle contraction increases palmitate esterification and oxidation and triacylglycerol oxidation. The American Journal of Physiology. 1998;275(5 Part 1):E888–E896.

- ^ a b Lafontan M., Langin D. Lipolysis and lipid mobilization in human adipose tissue. Prog. Lipid Res. 2009;48:275–297.

- ^ a b Jaworski K., Sarkadi-Nagy E., Duncan R.E., Ahmadian M., Sul H.S. Regulation of triglyceride metabolism. IV. Hormonal regulation of lipolysis in adipose tissue. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2007;293:G1–G4.

- ^ Mi-Jeong Lee,Susan K. Fried.Depot-Specific Biology of Adipose Tissues: Links to Fat Distribution and Metabolic Risk.Book Editor(s):Todd Leff,James G. Granneman.

- ^ P Arner 1.Differences in lipolysis between human subcutaneous and omental adipose tissues.Ann Med. 1995 Aug;27(4):435-8.

- ^ Peters S. J., Dyck D. J., Bonen A., Spriet L. L. Effects of epinephrine on lipid metabolism in resting skeletal muscle. The American Journal of Physiology. 1998;275(2 Part 1):E300–E309.

- ^ Dyck D. J., Bonen A. Muscle contraction increases palmitate esterification and oxidation and triacylglycerol oxidation. The American Journal of Physiology. 1998;275(5 Part 1):E888–E896.

- ^ alanian J.L., Tunstall R.J., Watt M.J., Duong M., Perry C.G.R., Steinberg G.R., Kemp B.E., Heigenhauser G.J.F., Spriet L.L. Adrenergic regulation of HSL serine phosphorylation and activity in human skeletal muscle during the onset of exercise. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2006;291:1094–1099.

- ^ Zimmermann R., Strauss J.G., Haemmerle G., Schoiswohl G., Birner-Gruenberger R., Riederer M., Lass A., Neuberger G., Eisenhaber F., Hermetter A., et al. Fat mobilization in adipose tissue is promoted by adipose triglyceride lipase. Science. 2004;306:1383–1386.

- ^ Villena J.A., Roy S., Sarkadi-Nagy E., Kim K.H., Sul H.S. Desnutrin, an adipocyte gene encoding a novel patatin domain-containing protein, is induced by fasting and glucocorticoids: Ectopic expression of desnutrin increases triglyceride hydrolysis. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:47066–47075.

- ^ Petridou A., Chatzinikolaou A., Avloniti A., Jamurtas A., Loules G., Papassotiriou I., Fatouros I., Mougios V. Increased triacylglycerol lipase activity in adipose tissue of lean and obese men during endurance exercise. J. Clin. Endocrinol.

- ^ Ranallo R.F., Rhodes E.C. Lipid metabolism during exercise. Sports Med. 1998;26:29–42.

- ^ Campbell J, Martucci AD, Green GR. Plasma albumin as an acceptor of free fatty acids. Biochem J. 1964;93:183–189.

- ^ Arner P., Kriegholm E., Engfeldt P., Bolinder J. (1990). Adrenergic regulation of lipolysis in situ at rest and during exercise. J. Clin. Invest. 85, 893–898

- ^ Galbo H., Houston M. E., Christensen N. J., Holst J. J., Nielsen B., Nygaard E., et al. (1979). The effect of water temperature on hormonal response to prolonged swimming. Acta Physiol. Scand. 105, 326–337

- ^ Steven M Frank 1, Christine G Cattaneo, Mary Beth Wieneke-Brady, Hossam El-Rahmany, Neeraj Gupta, Joao A C Lima, David S Goldstein.Threshold for adrenomedullary activation and increased cardiac work during mild core hypothermia.Clin Sci (Lond). 2002 Jan;102(1):119-25.

- ^ a b S M Frank 1, M S Higgins, L A Fleisher, J V Sitzmann, H Raff, M J Breslow.Adrenergic, respiratory, and cardiovascular effects of core cooling in humans.Am J Physiol. 1997 Feb;272(2 Pt 2):R557-62.

- ^ Horowitz J. F., Leone T. C., Feng W., Kelly D. P., Klein S. (2000). Effect of endurance training on lipid metabolism in women: a potential role for PPARα in the metabolic response to training. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 279, 348–355

- ^ Kelley DE, Kuller LH, McKolanis TM, Harper P, Mancino J, Kalhan S. Effects of moderate weight loss and orlistat on insulin resistance, regional adiposity, and fatty acids in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2004; 27: 33–40.

- ^ Ross R, Janssen I, Dawson J, Kungl AM, Kuk JL, Wong SL et al. Exercise-induced reduction in obesity and insulin resistance in women: a randomized controlled trial. Obes Res 2004; 12: 789–798.

- ^ Weinsier RL, Hunter GR, Gower BA, Schutz Y, Darnell BE, Zuckerman PA. Body fat distribution in white and black women: different patterns of intraabdominal and subcutaneous abdominal adipose tissue utilization with weight loss. Am J Clin Nutr 2001; 74: 631–636.

- ^ Gower BA, Weinsier RL, Jordan JM, Hunter GR, Desmond R. Effects of weight loss on changes in insulin sensitivity and lipid concentrations in premenopausal African American and White women. Am J Clin Nutr 2002; 76: 923–927.

- ^ Pasquali R, Gambineri A, Biscotti D, Vicennati V, Gagliardi L, Colitta D et al. Effect of long-term treatment with metformin added to hypocaloric diet on body composition, fat distribution, and androgen and insulin levels in abdominally obese women with and without the polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2000; 85: 2767–2774.

- ^ Alvarez GE, Davy BM, Ballard TP, Beske SD, Davy KP. Weight loss increases cardiovagal baroreflex function in obese young and older men. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2005; 289: E665–E669.

- ^ Rice B, Janssen I, Hudson R, Ross R. Effects of aerobic or resistance exercise and/or diet on glucose tolerance and plasma insulin levels in obese men. Diabetes Care 1999; 22: 684–691.

- ^ Weits T, van der Beek EJ, Wedel M, Hubben MW, Koppeschaar HP. Fat patterning during weight reduction: a multimode investigation. Neth J Med 1989; 35: 174–184.

- ^ Okura T, Tanaka K, Nakanishi T, Lee DJ, Nakata Y, Wee SW et al. Effects of obesity phenotype on coronary heart disease risk factors in response to weight loss. Obes Res 2002; 10: 757–766

- ^ Fujioka S, Matsuzawa Y, Tokunaga K, Kawamoto T, Kobatake T, Keno Y et al. Improvement of glucose and lipid metabolism associated with selective reduction of intra-abdominal visceral fat in premenopausal women with visceral fat obesity. Int J Obes 1991; 15: 853–859.

- ^ Janssen I, Ross R. Effects of sex on the change in visceral, subcutaneous adipose tissue and skeletal muscle in response to weight loss. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 1999; 23: 1035–1046.

- ^ Tchernof A, Nolan A, Sites CK, Ades PA, Poehlman ET. Weight loss reduces C-reactive protein levels in obese postmenopausal women. Circulation 2002; 105: 564–569.

- ^ Thong FS, Hudson R, Ross R, Janssen I, Graham TE. Plasma leptin in moderately obese men: independent effects of weight loss and aerobic exercise. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2000; 279: E307–E313.

- ^ a b Tiikkainen M, Bergholm R, Vehkavaara S, Rissanen A, Hakkinen AM, Tamminen M et al. Effects of identical weight loss on body composition and features of insulin resistance in obese women with high and low liver fat content. Diabetes 2003; 52: 701–707.

- ^ Ross R, Dagnone D, Jones PJ, Smith H, Paddags A, Hudson R et al. Reduction in obesity and related comorbid conditions after dietinduced weight loss or exercise-induced weight loss in men. A randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med 2000; 133: 92–103.

- ^ Gambineri A, Pagotto U, Tschop M, Vicennati V, Manicardi E, Carcello A et al. Anti-androgen treatment increases circulating ghrelin levels in obese women with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Endocrinol Invest 2003; 26: 629–634.

- ^ Park HS, Sim SJ, Park JY. Effect of weight reduction on metabolic syndrome in Korean obese patients. J Korean Med Sci 2004; 19: 202–208.

- ^ Nakamura M, Tanaka M, Kinukawa N, Abe S, Itoh K, Imai K et al. Association between basal serum and leptin levels and changes in abdominal fat distribution during weight loss. J Atheroscler Thromb 2000; 6: 28–32.

- ^ Park HS, Lee K. Greater beneficial effects of visceral fat reduction compared with subcutaneous fat reduction on parameters of the metabolic syndrome: a study of weight reduction programmes in subjects with visceral and subcutaneous obesity. Diabet Med 2005; 22: 266–272.

- ^ Okura T, Nakata Y, Lee DJ, Ohkawara K, Tanaka K. Effects of aerobic exercise and obesity phenotype on abdominal fat reduction in response to weight loss. Int J Obes (London) 2005; 29: 1259–1266.

- ^ Pare A, Dumont M, Lemieux I, Brochu M, Almeras N, Lemieux S et al. Is the relationship between adipose tissue and waist girth altered by weight loss in obese men? Obes Res 2001; 9: 526–534.

- ^ Kelley DE, Kuller LH, McKolanis TM, Harper P, Mancino J, Kalhan S. Effects of moderate weight loss and orlistat on insulin resistance, regional adiposity, and fatty acids in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2004; 27: 33–40.

- ^ Tiikkainen M, Bergholm R, Rissanen A, Aro A, Salminen I, Tamminen M et al. Effects of equal weight loss with orlistat and placebo on body fat and serum fatty acid composition and insulin resistance in obese women. Am J Clin Nutr 2004; 79: 22–30.

- ^ Kim DM, Yoon SJ, Ahn CW, Cha BS, Lim SK, Kim KR et al. Sibutramine improves fat distribution and insulin resistance, and increases serum adiponectin levels in Korean obese nondiabetic premenopausal women. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2004; 66 (Suppl 1): S139–S144.

- ^ Kamel EG, McNeill G, Van Wijk MC. Change in intra-abdominal adipose tissue volume during weight loss in obese men and women: correlation between magnetic resonance imaging and anthropometric measurements. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 2000; 24: 607–613.

- ^ Yip I, Go VL, Hershman JM, Wang HJ, Elashoff R, DeShields S et al. Insulin–leptin–visceral fat relation during weight loss. Pancreas 2001; 23: 197–203.

- ^ Jensen MD. Gender differences in regional fatty acid metabolism before and after meal ingestion. J. Clin. Invest. 1995;96:2297–2303.

- ^ Jensen MD, Johnson CM. Contribution of leg and splanchnic free fatty acid (FFA) kinetics to postabsorptive FFA flux in men and women. Metabolism. 1996;45:662–666.

- ^ Basu A, et al. Systemic and regional free fatty acid metabolism in type 2 diabetes. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2001;280:E1000–E1006.

- ^ Meek S, Nair KS, Jensen MD. Insulin regulation of regional free fatty acid metabolism. Diabetes. 1999;48:10–14.

- ^ Swift D.L., McGee J.E., Earnest C.P., Carlisle E., Nygard M., Johannsen N.M. The Effects of Exercise and Physical Activity on Weight Loss and Maintenance. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2018;61:206–213.

- ^ Cureton T. The Effect of Gymnastics upon Boys. College Coaches Gymnastic Clinic; Sarasota, FL, USA: 1954. Unpublished Paper.

- ^ Kireilis R.W., Cureton T.K. The relationships of external fat to physical education activities and fitness tests. Res. Q. Am. Assoc. Healthphys. Educ. Recreat. 1947;18:123–134.

- ^ Yuhasz M.S. The Effects of Sports Training on Body Fat in Man with Predictions of Optimal Body Weight. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign; Champaign, IL, USA: 1962.

- ^ Mohr D.R. Changes in Waistline and Abdominal Girth and Subcutaneous Fat Following Isometric Exercises. Res. Q. 1965;36:168–173.

- ^ Noland M., Kearney J.T. Anthropometric and densitometric responses of women to specific and general exercise. Res. Q. 1978;49:322–328.

- ^ Olson A.L., Edelstein E. Spot reduction of subcutaneous adipose tissue. Res. Q. 1968;39:647–652.

- ^ Bartness TJ, Vaughan CH, Song CK. Sympathetic and sensory innervation of brown adipose tissue. Int J Obes (Lond) 2010b;34(Suppl 1):S36–42.

- ^ Cao Y. Adipose tissue angiogenesis as a therapeutic target for obesity and metabolic diseases. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2010;9:107–115.

- ^ Rupnick MA, et al. Adipose tissue mass can be regulated through the vasculature. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:10730–10735.

- ^ Coppack SW, Fisher RM, Gibbons GF, Humphreys SM, McDonough MJ, Potts JL, et al. Postprandial substrate deposition in human forearm and adipose tissues in vivo. Clin Sci. 1990

- ^ Frayn KN, Karpe F. Regulation of human subcutaneous adipose tissue blood flow. Int J Obes. 2014

- ^ Wilhelm EN, González-Alonso J, Parris C, Rakobowchuk M. Exercise intensity modulates the appearance of circulating microvesicles with proangiogenic potential upon endothelial cells. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2016;311:p297–310.

- ^ Van Pelt DW, Guth LM, Horowitz JF. Aerobic exercise elevates markers of angiogenesis and macrophage IL-6 gene expression in the subcutaneous adipose tissue of overweight-to-obese adults. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2017;123:1150–9.

- ^ Ludzki AC, Pataky MW, Cartee GD, Horowitz JF. Acute endurance exercise increases Vegfa mRNA expression in adipose tissue of rats during the early stages of weight gain. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2018;43:751–4.

- ^ Lee HJ. Exercise training regulates angiogenic gene expression in white adipose tissue. J Exerc Rehabil. 2018;14:16–23.

- ^ Bente Stallknecht 1, Flemming Dela, Jørn Wulff Helge.Are blood flow and lipolysis in subcutaneous adipose tissue influenced by contractions in adjacent muscles in humans?.Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2007 Feb;292(2):E394-9.

- ^ Ilkka Heinonen 1, Marco Bucci, Jukka Kemppainen, Juhani Knuuti, Pirjo Nuutila, Robert Boushel, Kari K Kalliokoski.Regulation of subcutaneous adipose tissue blood flow during exercise in humans.J Appl Physiol (1985). 2012 Mar;112(6):1059-63.

- ^ Kurpad A, Khan K, Macdonald I, Elia M. Haemodynamic responses in muscle and adipose tissue and whole body metabolic responses during norepinephrine infusions in man. J Auton Nerv Syst 54: 163–170, 1995.

- ^ Stallknecht B, Lorentsen J, Enevoldsen LH, Bülow J, Biering-Sørensen F, Galbo H, Kjær M. Role of the sympathoadrenergic system in adipose tissue metabolism during exercise in humans. J Physiol Lond 536: 283–294, 2001.

- ^ Bartness TJ, Vaughan CH, Song CK. Sympathetic and sensory innervation of brown adipose tissue. Int J Obes (Lond) 2010b;34(Suppl 1):S36–42.

- ^ N J Rothwell, M J Stock.Influence of noradrenaline on blood flow to brown adipose tissue in rats exhibiting diet-induced thermogenesis.Pflugers Arch. 1981 Mar;389(3):237-42.

- ^ Pasarica M, Sereda OR, Redman LM, Albarado DC, Hymel DT, Roan LE, et al. Reduced adipose tissue oxygenation in human obesity evidence for rarefaction, macrophage chemotaxis, and inflammation without an angiogenic response. Diabetes. 2009

- ^ Stefania Camastracorresponding author1 and Ele Ferrannini2.Role of anatomical location, cellular phenotype and perfusion of adipose tissue in intermediary metabolism: A narrative review.Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2022; 23(1): 43–50.

- ^ Coppack SW, Fisher RM, Gibbons GF, Humphreys SM, McDonough MJ, Potts JL, Frayn KN. Postprandial substrate deposition in human forearm and adipose tissues in vivo. Clin Sci (Lond) 79: 339–348, 1990.

- ^ Summers LKM, Samra JS, Humphreys SM, Morris RJ, Frayn KN. Subcutaneous abdominal adipose tissue blood now: Variation within and between subjects and relationship to obesity. Clin Sci. 1996

- ^ Jansson PA, Larsson A, Smith U, Lonnroth P: Glycerol production in subcutaneous adipose tissue in lean and obese humans. J Clin Invest 89: 1610–1617, 1992

- ^ Andersson J, Karpe F, Sjöström LG, Riklund K, Söderberg S, Olsson T. Association of adipose tissue blood flow with fat depot sizes and adipokines in women. Int J Obes 36: 783–789, 2012.

- ^ Jansson PA, Larsson A, Lönnroth PN. Relationship between blood pressure, metabolic variables and blood flow in obese subjects with or without non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Eur J Clin Invest 28: 813–818, 1998.

- ^ Gastaldelli A, Cusi K, Pettiti M, Hardies J, Miyazaki Y, Berria R, et al. Relationship Between Hepatic/Visceral Fat and Hepatic Insulin Resistance in Nondiabetic and Type 2 Diabetic Subjects. Gastroenterology. 2007

- ^ Begovatz P, Koliaki C, Weber K, Strassburger K, Nowotny B, Nowotny P, et al. Pancreatic adipose tissue infiltration, parenchymal steatosis and beta cell function in humans. Diabetologia. 2015

- ^ Voros G., et al. Modulation of angiogenesis during adipose tissue development in murine models of obesity. Endocrinology. 2005;146:4545–4554.

- ^ Eriksson A., et al. Placenta growth factor-1 antagonizes VEGF-induced angiogenesis and tumor growth by the formation of functionally inactive PlGF-1/VEGF heterodimers. Cancer Cell. 2002;1:99–108.

- ^ Inuzuka H., et al. Differential regulation of immediate early gene expression in preadipocyte cells through multiple signaling pathways. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1999;265:664–668.

- ^ Seida A., et al. Serum bFGF levels are reduced in Japanese overweight men and restored by a 6-month exercise education. Int. J. Obes. Relat. Metab. Disord. 2003;27:1325–1331.

- ^ Shang C.A., Thompson B.J., Teasdale R., Brown R.J., Waters M.J. Genes induced by growth hormone in a model of adipogenic differentiation. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2002;189:213–219.

- ^ J Bülow, J Madsen.Human adipose tissue blood flow during prolonged exercise II.Pflugers Arch. 1978 Aug 25;376(1):41-5.

- ^ J Bülow.Subcutaneous adipose tissue blood flow and triacylglycerol-mobilization during prolonged exercise in dogs.Pflugers Arch. 1982 Jan;392(3):230-4.

- ^ a b Ferguson RA, Ball D, Krustrup P, Aagaard P, Kjaer M, Sargeant AJ, Hellsten Y, Bangsbo J. Muscle oxygen uptake and energy turnover during dynamic exercise at different contraction frequencies in humans. J Physiol 536: 261–271, 2001.

- ^ A Collin 1, Y Lebreton, M Fillaut, A Vincent, F Thomas, P Herpin.Effects of exposure to high temperature and feeding level on regional blood flow and oxidative capacity of tissues in piglets.Exp Physiol. 2001 Jan;86(1):83-91.

- ^ Lossec 1, C Duchamp, Y Lebreton, P Herpin.Postnatal changes in regional blood flow during cold-induced shivering in sow-reared piglets.Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 1999 Jun;77(6):414-21.

- ^ Naoto Fujii 1, Tatsuro Amano 2, Glen P Kenny 3, Yasushi Honda 1, Narihiko Kondo 4, Takeshi Nishiyasu 1.Nicotinic receptors modulate skin perfusion during normothermia, and have a limited role in skin vasodilatation and sweating during hyperthermia.Exp Physiol. 2019 Dec;104(12):1808-1818.

- ^ Naoto Fujii 1, Brendan D McNeely 1, Sarah Y Zhang 1, Yasmine C Abdellaoui 1, Mercy O Danquah 1, Glen P Kenny 1.Activation of protease-activated receptor 2 mediates cutaneous vasodilatation but not sweating: roles of nitric oxide synthase and cyclo-oxygenase.Exp Physiol. 2017 Feb 1;102(2):265-272.

- ^ Crandall CG, Etzel RA & Johnson JM (1997). Evidence of functional β‐adrenoceptors in the cutaneous vasculature. Am J Physiol 273, p038–1043.

- ^ Medow MS, Taneja I & Stewart JM (2007). Cyclooxygenase and nitric oxide synthase dependence of cutaneous reactive hyperemia in humans. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 293, p25–432.

- ^ Hodges GJ, Kellogg DL & Johnson JM (2015). Effect of skin temperature on cutaneous vasodilator response to the β‐adrenergic agonist isoproterenol. J Appl Physiol 118, 898–903.

- ^ Fujii, N., Louie, J. C., McNeely, B. D., Amano, T., Nishiyasu, T., & Kenny, G. P. (2017a). Mechanisms of nicotine-induced cutaneous vasodilation and sweating in young adults: Roles for KCa, KATP, and KV channels, nitric oxide, and prostanoids. Applied Physiology, Nutrition and Metabolism, 42, 470–478.

- ^ a b Izumi, H., & Karita, K. (1992). Axon reflex flare evoked by nicotine in human skin. Japanese Journal of Physiology, 42, 721–730.

- ^ Johnson, J. M., Minson, C. T., & Kellogg, D. L., Jr. (2014). Cutaneous vasodilator and vasoconstrictor mechanisms in temperature regulation. Comprehensive Physiology, 4, 33–89.

- ^ Smith, C. J., & Johnson, J. M. (2016). Responses to hyperthermia. Optimizing heat dissipation by convection and evaporation: Neural control of skin blood flow and sweating in humans. Autonomic Neuroscience, 196, 25–36.

- ^ Wong, B. J., & Hollowed, C. G. (2017). Current concepts of active vasodilation in human skin. Temperature, 4, 41–59.

- ^ Caroline J Smith 1, John M Johnson 2.Responses to hyperthermia. Optimizing heat dissipation by convection and evaporation: Neural control of skin blood flow and sweating in humans.Auton Neurosci. 2016 Apr;196:25-36.